Trouble at the top… or not? Medvedev and Putin… January 14, 2009

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Russia.16 comments

Intriguingly the Financial Times this week has a piece on a degree of discord between Medvedev and Putin. It reports that:

Dmitry Medvedev, the Russian president, on Sunday took another apparent swipe at Vladimir Putin, rebuking the prime minister’s government for moving too slowly to alleviate the country’s economic crisis.

And that although…

Most Russians had believed Mr Medvedev would play second fiddle to Mr Putin, who named him as his chosen successor ahead of presidential elections last year…[although] several attempts by Mr Medvedev to pursue independent policies have been thwarted, Kremlin watchers have noted a new assertiveness in the president of late.

The FT certainly has a bee in its bonnet on this issue. For on December 31 they reported that:

…in the six days since Dmitry Medvedev, Russia’s president, described his feelings about taking the oath of office in May, the corridors of power have been buzzing.

“The final responsibility for what happens in the country and for the important decisions taken would rest on my shoulders alone and I would not be able to share this responsibility with anyone,” Mr Medvedev told an interviewer.

And that:

For a normal president in a normal country, such a remark would have been a statement of the obvious. But to a select few, it was a “dog whistle”, a message audible only to those Mr Medvedev wanted to hear.

And on the 1st of August one could also read that:

The relationship between the two men [Putin and Medvedev] has been mostly harmonious, but the new president would clearly like to move out from under his predecessor’s shadow.

To add weight to his normally soft-spoken persona, Mr Medvedev has recently begun mimicking Mr Putin’s tough guy television style, lacing his official-sounding pronouncements with slang and street jargon. There was also plenty of finger jabbing, fist clenching and table slamming as he ran a carefully staged and nationally televised meeting in Gagarin between the town’s small business owners and a contrite looking group of government officials – driven in from Moscow especially for the purpose of being public whipping boys – as Mr Medvedev announced a new plan to fight official corruption.

Talking about rhetoric, Medvedev during the Russian Georgian conflict was strikingly harsh and his overt use of slang – and wow, do I sound prurient as I read this back – very evident.

It’s hard to know what the truth of this matter is. But it is hardly strange that Medvedev, proxy or no, would seek to carve out his own niche or that he might with time come to enjoy both the trappings and the substance of his office. Can’t help though and wonder whether there is any great substance to all this.

Still, in a year when the US Presidency might be thought to be of a certain fascination, and it is – it is, no harm in casting an eye eastwards every once in a while at the Russian Presidency.

Context. Or How to Ignore it When Making a Documentary November 11, 2008

Posted by Garibaldy in Communism, Film and Television, History, Russia.72 comments

So this is my review of the BBC programme I flagged up yesterday, World War II Behind Closed Doors: Stalin, the Nazis and the West. I stress it is my review because I suspect that the other authors on Cedar Lounge Revolution might disagree strongly with my presentation of the events I am about to discuss. I was going to post it only on my own blog, but it seemed silly to flag it up here and then not publish the review here.

Tonight’s programme was the first of six analysing the history of Soviet diplomacy during World War II. It opened with a claim that Stalin had some strange friendships. Stalin telling Churchill he killed the Kulaks when Churchill asked, cutting to Churchill looking shocked; and Roosevelt stating that he did not believe the Soviets had done something, presumably bad. The voiceover was clear to stress that its reconstructions were based on archival documents. Stalin had been introduced as the supreme leader of the Soviet Union, and a tyrant responsible for the deaths of millions, with accompanying depiction of a prisoner being shoved into a cell for execution. Churchill, however, was not introduced as the prime minister of an Empire that spanned the globe, that had in the last several decades since the Bolshevik Revolution (and of course before) used terror and massacre of civilians to frustrate the democratic will of several peoples for independence, and in which Churchill had been personally involved. No mention then of the Black and Tans or Amritsar or bombing civilians in Iraq, of keeping the world’s second most populous nation and one of its most ancient cultures in subjection. We might see that as the first absence of context, but let’s be generous, and say that this might turn up in future episodes – however unlikely we know that to be.

The action then moved to arrival on August 23rd 1939 of the German Foreign Minister, Ribbentrop, in Moscow to negotiate a non-aggression pact with Stalin. One of the questions from my post on my own blog in anticipation of tonight’s show was immediately answered. Not only was there no mention of the fact that Stalin had offered France and the UK a military alliance to stop Hitler to which he was prepared to commit one million men including armour, artillery and air support, there was no mention at all of the fact that these negotiations had even taken place! Nor was there any mention of the western powers sitting on their hands during the Spanish Civil War, and attempting to frustrate Soviet efforts to help the democratically-elected Republican government, nor even of appeasement. Given that the western powers had done nothing to halt the rise of the Nazis – in fact quite the opposite, caving to them over Czechoslovakia at meetings from which the USSR was excluded, the Soviets decided to look after number one. Is it all that hard to blame them, given the known hostility of the western powers to communism, and their habit of breaking guarantees in the face of fascist aggression? Yet none of these issues – essential to understand the Pact – were mentioned. It’s hardly like the producers were unaware of them – I am sure someone on their team knows how to use Wikipedia. No, this was a deliberate editorial decision in order to sharpen the story they wanted to tell. Unfortunately it amounts to such a sin of omission as to falsify the history of the events explored. Just text, not context.

There were plenty of moments designed to make one feel queasy. Images of Nazis and Commies wining and dining themselves, celebrating their alliance in opulent splendour. In fact, pretty standard state dinners – though perhaps a little more flash than most – and filled with the usual diplomatic pleasantries and toasts. I am sure we could find similar examples involving the Germans, Italians, Spanish, Japanese, Americans, French and the British in the same period. Without this context, these incidents, especially the toasts, look much more repulsive than they were. Similarly the account of the Soviets and Germans cooperating in establishing the new border in Poland. Demarcating borders is hardly an unusual occurrence.

Nor was there any discussion of the possibility that the Pact was designed to play for time. Stalin’s hidden remarks about the USSR not allowing Germany to be put down could easily be interpreted as a move to convince them that the Soviets represented no threat, and to put off the prospect of war. Certainly, as the programme pointed out, the Germans lied to the Soviets. Why not the other way around? The fact that the USSR provided the Germans with a base is shocking. But at the same time, they clearly did the bare minimum. Denying them the base where they wanted it, refusing to allow them ashore, and rendering the base much less effective. The lack of talking historian heads in this type of documentary allows the narrative to flow more easily, but denies the opportunity to explore different interpretations, but one thing that did come out clearly was Stalin’s skill as a negotiator, forcing Hitler into doing things more on Soviet terms.

The depressing stories of the deportations from Poland of suspect populations again lacked context. While the programme makers did acknowledge that the targeting of the Polish middle class was an ideological and not racial move, they failed to mention that during World War II, the rounding up of suspect populations was par for the course – just ask Japanese-Americans. There were of course strategic implications here too in the event of an outbreak of war, and moving suspects and their families far from the border made sound strategic sense. Similarly the brutal events in Katyn and its equivalent. I am not justifying what went on here, but I am seeking to understand it properly. I feel the programme makers ought to have discussed more the fears of war, invasion and abandonment that were so central to Soviet choices at this time – they only really got mentioned after the fall of France. After all, the choice to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki is never mentioned in isolation from the fears of US deaths in Japan in such programmes. The Soviet help delivered to the Germans was delivered out of fear.

Fear it seems also played a large part Stalin’s mistake in refusing to take the advice of his generals regarding military preparations for the coming war with Germany. He did not want to provoke the Germans into launching the war. He also believed that Hitler was playing diplomatic games of the sort Stalin had used to pressurise Hitler when he moved troops closer to the USSR. It was a grave error of judgment, but the resilience of the peoples of the USSR and the leadership and reorganisation provided by the Communists, along with allied aid, prevented the collapse. We can only be grateful for that fact.

The first mention of the possibility of an alliance between the Soviet Union and the UK was at the end of the programme, which said Stalin turned to it in desperation, setting up next week’s programme. This complete lack of discussion of the dilpomatic history of the 1930s was I feel dishonest of the programme makers, and gave a completely misleading impression of why Soviet diplomacy followed the path it did, and poisoned not only this programme in the series, but will most likely poison the series itself.

Overall then, certainly an interesting programme, as all programmes that give you the words of the participants must be. Certainly I learnt more about the mistakes of the Soviet leadership, the extent of Soviet cooperation with the Germans, and the treatment of the Polish aristocracy (themselves, it must be said, no saints). Nevertheless, I was disappointed with the programme. The absence of the context, of the background to the Pact, ruined the programme for me, as I spent the rest of the time viewing it with a jaundiced eye thinking “what about this? what about that?” No programme will be perfect, but the misleading nature of this one was a big let-down.

Russian rhetoric and grand narratives… August 13, 2008

Posted by WorldbyStorm in International Politics, Russia.4 comments

Perhaps a few small cheers for the EU and Sarkozy in particular for avoiding the superheated rhetoric from Washington and being ready to move in (granted when Russia was willing to deal) and broker the ceasefire. Although perhaps a few less if one considers a basic question posed in the New York Times:

Who will enforce a cease-fire — the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, which currently monitors South Ossetia; the United Nations, which monitors Abkhazia; or some other organization, like the European Union?

Anyhow, we know – or ought to know – that diplomats, leaders, whatever are as human as the rest of us. But to hear on Channel 4 News last night the President of Russia call his Georgian opposite number ‘scum’ has a certain… chilling effect. Granted this was transmuted to the rather less pointed ‘lunatic’ in the Guardian. But…

It’s not that emotion is uncalled for (although one might reasonably ask of someone linked to a government that has carried out a raft of actions in Chechnya whether there is a certain lack of perspective at work here), the last week or so has seen deaths on both sides. Nor is a depth of bitterness at the collapse of the Soviets, not so much as an ideological structure as a governing structure with all that that entailed for Russia itself, and the outworkings of that collapse difficult to understand. Neither is it impossible to see how a centre, any centre, would find the provocations, or even – let’s be frank – the (from their viewpoint) entirely reasonable actions of Georgia in its bid to shore up its own territorial sovereignty, irritating in the extreme.

But when this emotion is articulated not in the smooth language of international diplomacy but in a blunt and deliberate fashion then it is most likely a deliberate ploy, one calculated to send a message to the Georgian government and to Russias friends and foes.

Medvedev is a clever individual, one doesn’t reach even the nominal apex of Russian power in this decade without being clever. And beyond that he is an intelligent and thoughtful man, perhaps more thoughtful than his predecessor. But there is no magnanimity in this victory – and it is a victory. This is his war, as much as the second Chechen war was that of his nominal predecessor. Putin, not unwisely, made sure that he was visible on the ground. But it is Medvedev who meets Sarkozy, who becomes the face of Russia to the rest of the world. And perhaps that tells us something interesting about how power is being dispersed very slightly within Russia today.

(Of course there may be greater calculation at work here. No harm for Medvedev to go forward into the glare of the international media and if things turn particularly sour he can be blamed as the man who let it all go wrong. But I don’t think that’s what is playing out here).

But let’s pull back from that a moment. Because it’s quite a world we live in when one of the three or four remaining superpowers uses language this harsh, this indifferent to tone. And I think this is important, not least because rhetoric in international affairs is often as important as substance. It also points to something that we keep hearing from various sources. Russia has no guiding ideology distinct from say the United States or any given European power. It’s just another capitalist power. Unlike the United States it has few pretensions, rhetorical or otherwise, to clothe itself in the trappings of an activist and expansionist democracy. And so, in a sense, what is left? It is placed in a curious position. Unlike say Germany which, while much smaller a country is not entirely dissimilar in terms of power and scope, was able in the post-War period to lock itself into the European project as a national narrative there is no grand narrative for Russia. Other that is than itself and it’s satellites and allies. And although one might – at a push – argue that its rhetoric on Serbia played to a pan-Slavic nationalist feeling, however inchoate and however unfulfilled in practice, that is hardly a substitute for the Soviet narrative.

And it is this loss, not merely of empire but of purpose, which I suspect fuels much of the bitterness of the rhetoric. Saakashvili is “scum” (and who knows? His actions in going into South Ossetia were lunatic, whatever previous provocations and however much he too is a prisoner of history), but somehow the language merely points up the limitations of Russian power. Surrounded by the ‘near abroad’, a near abroad which it dominates through proximity, in certain instances shared cultural values and ties and retained or increasing military or financial and economic power. Medvedev and Putin cannot, however much they might like to, appeal to Russia’s neighbours through the form of some new grand narrative, or at least not one that is clearly seen at this point. Russia does capitalism pretty well, but it will always lose out to the United States in the short to medium term in terms of putting an attractive face on that capitalism. And this is remarkably constraining. The great game is limited because the US still has something, however tattered and tarnished, to offer that makes it globally attractive (and globally reviled). China? Not so much, but its cleverly using soft power to make its case – the implicit case of all global or aspirant global powers – for it. Which leaves Russia, hemmed in by history, by its previous conquests and by its present conflicts.

[Speaking of the great game… I was intrigued to see the idea that we live in a multi-polar world bandied about again. That’s hardly news to anyone who reads the Guardian opinion pages, let alone Prospect, or Foreign Affairs. And it has been the situation certainly since remarkably soon after the demise of the Soviet Union. While Russia was down, if not out, China snuck in, as has India in a lower key way… and South America and Africa are producing their own local hegemons…]

What is frustrating is that it doesn’t have to be this way. The past five years had seen a more cautious and considered approach emerge under Putin. One that while far from the sweeping excesses and curious grandeur of the Soviet era, or the chaotic turns of the 1990s, allowed it to reshape itself as a sensible voice arguing for stability. Not exactly earth shattering, or even world changing, but something that might see it gain a certain respect. The most recent events may have set that back by years, perhaps even a decade or more. Or maybe all this will be forgotten and forgiven. Nothing is utterly intractable or inevitable. Long-time foes can become close partners, we merely have to look at the EEC/EU and the way that not-entirely-grand narrative has functioned across half a century to see that.

There are ways forward, some suggested by comments on here. One would be a serious effort by the EU and Russia to work more proactively jointly to stabilise security and cooperation in remaining areas of conflict, (thereby in some ways answering the question posed by the NYT – and for those who question why poachers should turn gamekeepers, well, isn’t that precisely what the EU has been about from day one?) an effort which would avoid the sort of zero sum approaches we have seen in Kosovo and now in South Ossetia. It’s not much of a grand narrative, but it might actually do some good on the ground away from the lofty and, as we’ve seen, not so lofty rhetoric of power politics.

Foreign Affairs journal, the US Presidential Candidates and Russia, going, going… Well, no, perhaps not. December 21, 2007

Posted by WorldbyStorm in International Politics, Russia, United States.16 comments

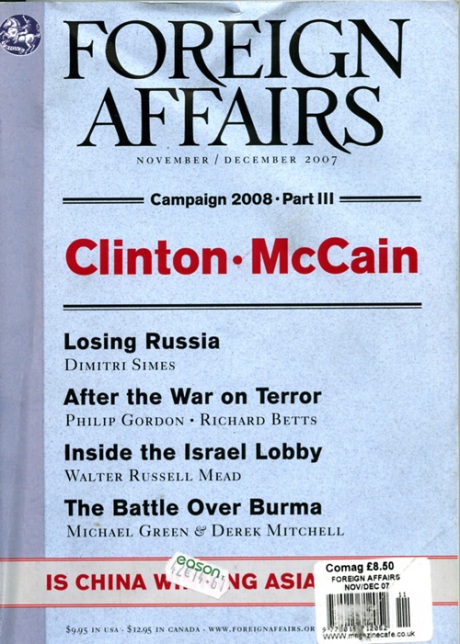

Interesting to see in the same week as Putin’s significant victory in the Russian elections an article by Dimitri Simes in Foreign Affairs journal.

Incidentally, Foreign Affairs is a great read. The last half year we’ve been treated to the ‘thoughts’ of the rival contenders for the US Presidency on foreign affairs. A dispiriting prospect I can tell you. Mitt Romney “Rising to a New Generation of Global Challenges” and telling us ‘we are a unique nation’… Barack Obama asserting that ‘today, we are again called to provide visionary leadership’, John McCain assures us that ‘since the dawn of our Republic, Americans have believed that our nation was created for a purpose, we are… ‘a people of great destinies’, and Hilary Clinton? Well actually she avoided the boosterism and gave a fairly solid and almost downbeat analysis of the situation… she concluded by noting that “Daniel Webster (secretary of state in 1825)… gloried not in American power but rather in the power of the American idea, the idea that ‘with wisdom and knowledge men may govern themselves’. And he urged his audience, and all Americans, to maintain this example and ‘take care that nothing weakens its authority with the world’.

Other than that you’ll find useful pieces on Burma, a rather entertaining and critical review of “The Israel Lobby” and some frankly bizarre thoughts on “After the War on Terror”. Which leads me back to Simes article.

Simes is President of the Nixon Centre, but let not that information put you off his central thesis. Realpolitik prevails.

In it he notes that the relationship following the fall of the Soviet Union was one where the US treated Russia as if it were a defeated nation. Yet as he points out Russia wasn’t defeated in any conventional sense. The USSR withdrew from Eastern Europe, it wasn’t forced. If anything the Soviet Union could probably have staggered on for a good decade more or longer. And he entirely dismisses the idea that the US ‘won’ the Cold War pointing out that ‘misunderstanding and misrepresentations of the end of the Cold War have been significant factors in fueling misguided U.S. policies towards Russia. Although Washington played an important role in hastening the fall of the Soviet Empire [i.e. Soviet influence in the Warsaw Pact countries], reformers in Moscow deserve far more credit than they generally receive’. He also makes the crucial point that if anything the U.S. ‘played even less of a role in bringing about the disintegration of the Soviet Union….by allowing pro-independence parties to compete and win in relatively free elections and refusing to use security forces decisively to remove them Gorbachev virtually assured that the Baltic states would leave the USSR. Russia itself delivered the final blow, by demanding institutional status equal to the other union republics. Gorbachev told the Politburo that permitting the change would spell ‘the end of empire’.’ [incidentally, for an analysis of this period you could do worse than read Virtual History (ed. Niall Ferguson, 1998) which has an excoriatingly conservative piece by Mark Almond which manages to simultaneously blame Germany and Europe for being too cynical in their dealings with the Warsaw Pact while also blaming Gorbachev for not being cynical enough and manipulating the CPSU in the aftermath of the failed coup in order to shore up his political position).

While this is fascinating, it is the subsequent relationship between the US and Russia which is of immediate interest.

Simes compares the Reagan/Bush administrations ‘respectful’ treatment of Gorbachev ‘without making concessions at the expense of US interests’ with ‘the Clinton administrations greatest failure… [which was its] decision to take advantage of Russian weakness’. Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott admitted that US officials ‘even exploited Yeltsin’s excessive drinkign during negotiations. Many Russians believed that the Clinton administration was doing the same with Russia writ large. The problem was that Russia eventually did sober up, and it remembered the night before angrily and selectively’. It’s fair to point out that Simes is probably seeing this through a Republican filter. Yet..

…it also has to be said, some of what was imposed on Russia in the 1990s was – and there is no other word for it – criminal and explains (in economic terms, as any good Marxist analysis would) the roots of the new Russia which flexes muscles unused for almost two decades and finds them in markedly better condition than most would have expected.

The unconstitutional attacks on the Duma both political and physical by Yeltsin arguably delegitimised the democracy process by effectively cutting out the representative element of the Russian people from the equation as the polity hurled itself headlong towards a fully executive Presidency. That those in the Duma took a line which was leftish, or perhaps more honestly populist-ish, is in a way neither here nor there. They fell foul – indirectly – to Washingtons ‘pressure…for the harsh and hugely unpopular monetary policies’. Collateral political damage if you will. The tragedy continued throughout the 1990s as NATO effectively ignored Russian objections with regards to Serbia. It worsened as the US began to perceive Russia not as near-ally, but as adversary, and aligned itself with former Soviet states such as Georgia.

But, all had changed by 2001. A new US President. A new global threat. Putin threw Russian weight behind US international efforts to curb Islamist terrorism (indeed the Russians had offered just such a joint approach as early as 1999 but were turned down by the US – not unreasonably the latter was in part influenced by the Chechen morass). Yet… despite the positive moves new issues arose. Georgia was joined by the Ukraine as another state where Russian influence was beginning to somewhat decline and US influence to increase. The latter was seen as a worrying development by the Russians. And it is fair to say that relations between Russia and the US have become frostier and frostier.

Simes notes that ‘despite these growing tensions, Russia has not yet become a U.S. adversary’. Indeed he argues that ‘most importantly the US must recognize that it no longer enjoys unlimited leverage over Russia. Today Washington simply cannot force its will on Moscow as it did in the 1990s’. Simes notes that ‘the power of the United States’ moral advantage has been damaged’.

And Simes argues that ‘numerous disagreements do not mean that Russia is an enemy’. It has not ‘invaded or threatened to invade its neighbours’. It does not ‘support any terrorist group at war with the US’. But ‘Putin [and Russia] is no longer willing to adjust their behaviour to fit U.S. preferences, particularly at the expense of their own interests’.

Here is the thing. Today Russia has no over-arching ‘global’ ideology, albeit there are nods towards the ancien regime in terms of rhetoric and iconography. It has transitioned from global co-hegemon to near failed state and back to effective Great Power. It now operates purely according to its own national interest. And curiously that could bring it into greater conflict with the de facto hegemon the US which does have a near global ideology, that of a certain strain of liberal democracy. Granted the latter is near rhetorical in many instances, but… as a prevailing socio-political narrative it is of great significance and underpins the sort of thinking exemplified by the statements of Obama, McCain and Clinton above.

But Russia has legitimate interests, has a zone of influence, and an appetite to play the great game. It seems to me that Gorbachev envisioned a partnership between the US and the USSR – perhaps even thought aspects of the latter could influence the former. That now seems unlikely if only because of the disparities in global power. But this is a world in which the unipolar is being replaced by the multipolar. Russia is once more a player, along with China and the EU. One can point to some other nations in South East Asia and South America which are moving to join them.

I don’t share the stance of some of the former CP parties which appear to see Russia as a sort of hobbled continuation of the Soviet Union and therefore tailor their argument to position it within a framework of malevolent US imperialism and profound Russian victimhood. I think that’s a self-serving analysis. The USSR was a political, not a national, entity. Russia is a national entity more than a political entity. It is also a state with neo-imperial pretensions of its own, particularly as regards the zone of influence. This demands that it is treated with the ‘respectful’ approach noted by Simes above. If anything – while there are clear dangers, particularly where there are misperceptions of divergent (but not antagonistic) national interests – the situation is an improvement on a hegemon which has over the last four years been proven to have significant limitations. A strong Russia can, almost counterintuitively, provide both balance and support for an international system that badly requires it. But this can also tip into essentially a continuation of ‘business as usual’ which is also profoundly cynical where the respective ‘powers’ carve up the cake as they see fit. That is something to be profoundly wary of. So, two and a half cheers for a stronger Russia. But let’s keep in mind that powers do what powers must. Still, caution at the United Nations is no harm after a period of willful and energetic abandon. The sooner the better some might say.

One year on, another victim of Putin’s Russia October 7, 2007

Posted by franklittle in Freedom of speech, media, Media and Journalism, Russia.6 comments

World by storm had an interesting post last week about the possibility of Russian President Vladimir Putin becoming Russian Prime Minister. In the course of commentary on the article, Eagle referred to the deaths of journalists in Russia over the last few years. There have also been numerous and well substantiated recent reports about the use of mental facilities for the detention of political opponents and dissidents.

Appropriate so that today is the first anniversary of the murder of Anna Politkovskaya, journalist with Novaya Gazeta, whose courageous reporting of the war in Chechnya depicting the suffering of the innocents at the hands of Russian and Chechen forces, was often a lone voice in the heavily censored and restricted Russian media. She was also a harsh critic of Putin, chiefly for his role in pushing Russia into a second, and far more brutal, war in Chechnya, but also for his contempt for civil liberties and personal freedoms. In it she warned:

“We are hurtling back into a Soviet abyss, into an information vacuum that spells death from our own ignorance. All we have left is the internet, where information is freely available. For the rest, if you want to go on working as a journalist, it’s total servility to Putin. Otherwise, it can be death, the bullet, poison or trial – whatever our special services, Putin’s guard dogs, see fit.”

It was her reporting from Chechnya that most affected me however. The interviews with terrified Russian conscripts. With a seemingly endless stream of refugees in the camps around Chechnya’s borders whose names she scrupulously noted to ensure they were not forgotten. The macabre attempts to identify the bodies of Russian soldiers so that they could be buried, doomed to defeat by bureaucracy, petty corruption and greed. Her efforts, and those of her publication, to successfully evacuate an old folks home from the middle of Grozny that had been callously abandoned by both sides. The images of a battered Grozny, with children scavenging for food in the courtyards of apartments whose rubble piles still held their neighbours.

Despite threats, beatings, a mock execution at the hands of Russian forces and one previous murder attempt, she persisted in her work until she was shot to death in the elevator of her apartment building in Moscow on October 7th of last year. Putin’s birthday coincidentally enough.

Some people have accused Putin’s intelligence services of having carried out her execution. A great deal of initial speculation centred on Russian backed Chechen Prime Minister Ramzan Kadyrov, a frequent target of Politkovskaya’s work whom she had described as Chechnya’s Stalin. She was working on an exposé of his security forces when she was killed and many of her colleagues in journalism still believe that it was people close to Kadyrov who had her killed for her work in exposing their corruption.

Putin’s investigators have blamed ‘outside forces’ who sought by killing her to destabilise the state and embarrass Putin. At the end of August they arrested a number of people including Chechen organised crime figures and former FSB agents and, curiously, leaked massed of information about them to the media.

As Dmitri Muatov, editor of Politkovskaya’s paper, said:

“The case of Anna Politkovskaya is falling apart; the intention is that it should come to nothing, to zero. This has been done by leaking information which should be kept secret. A couple of high-ranking people from different government structures, from the “siloviki” and special services, have leaked information about this case.

“They have distributed a list of the people detained. This is unprecedented. Why has this been done? Because there was an order to do it so that all the other participants in the case would be able to hide.

“All the photos and biographies, with police information about those detained, were published on the internet and in two tabloids.”

One year on, and no closer to justice.

The spirit and the letter of democracy. Putin’s Russia… October 2, 2007

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Democracy, Russia.23 comments

I’m enormously admiring of Vladmir Putin’s latest idea. As reported in the Guardian he has suggested that since he is debarred by the Russian Constitution from serving another term as President he might become Prime Minister instead. The funny thing is that a couple of weeks back I was thinking about him on foot of an interesting discussion on Splintered Sunrise on democracy and the thought struck me, ‘what if he simply switched over to Prime Minister’. Needless to say I dismissed it almost immediately. Which tells you, perhaps, why I am an anonymous blogger and he is President of all the Russians.

But even so, I have to admire the simplicity with which he puts forward his message. The same report noted that:

…Putin yesterday gave the strongest hint yet that he will remain at the centre of power in Russia for the forseeable future, saying the possibility of him becoming prime minister after the presidential election in March was “entirely realistic”.

I like that ‘entirely realistic’. It is the understatement that is so telling. There he is, weighing up his future and that of millions of Russians. Should he take up golf like Clinton? Middle East peace making like Blair? No, presumably those would not be ‘entirely realistic’ options.

It gets better. When asked about the nature of any such Premiership he noted that:

“Heading the government is a realistic idea,” Mr Putin told the party’s congress when asked about his plans. He added that it was “early” to be discussing himself as a candidate, but he would be prepared to take the prime minister’s post on two conditions: that United Russia won the parliamentary poll and that a “decent, competent and effective person with whom I could work” was elected as president in spring 2008.

Again, got to love the ‘decent, competent…etc, etc’. I imagine that if he becomes Prime Minister it will be very much in the nature of an executive premiership. The levers of power will slip over to same in the next year or so. But in a way such bluntness is heartening. There is little beating around the bush with Putin. One gets exactly what one sees. And, naturally, he has an eye on the Presidency in the long term. He can run again after the next President. Presumably we might see a switch back to a more ‘Presidential’ model at that point. Or as was reported:

Mr Mukhin said that if Mr Putin became prime minister it was “entirely possible” that with support from United Russia in the parliament he would change the law to increase the powers of the premiership vis-à-vis the president. “Putin promised not to change the constitution before he leaves the presidency, but he doesn’t have any obligations beyond that,” he noted.

So, we have Putin in near perpetuity. And all of it done in such a way that the letter of democracy is entirely intact. One might even argue that the spirit, although slightly ruffled around the edges remains there or thereabouts, particularly if Putin doesn’t change the constitution.

I’m reminded, for some reason, of what Australian cultural commentator Donald Horne wrote in his book “The Public Culture” about ‘myth’s’ (in the semiotic sense) of democracy.

“The very way in which the ‘myth’ of representative democracy ‘legitimates’ state power int he name of the people can distract citizens from the realities of political power. It can suggest that since they all have the vote and use their votes with relatively equal weights, there must be in their society an equality in the distribution of power. This illusion is strengthened by beliefs in the centrality of government – as if ‘power’ is uniquely resident within the government, which is represented as having an independent (sometimes arbitrating) existence and of representing an agreed common good… the setpiece battles of presidential systems that can begin the day after a president is sworn in (and that in the US take over the last year of a presidential term) can weaken faith in government but not by puttign politics out among citizens. In watching the sentsations of party politics citizens are encouraged to believe that political discussion is being carried out for them…the electoralisation of politics can suggest that a citizen’s only task is to vote; it can even suggest that there is something undemocratic in protest by citizens against the government, because the government is the repository of the people’s will…’

I think Horne is onto something here and it has particular applicability to both the Russian, and the US, systems of government. The executive Presidency engenders precisely this sense that protest is illegitimate because state and President become enmeshed in a web of significations which feed off and support each other. The problem is arguably worse in Russia due to the centralising tendencies of the Putin years (although that tendency is understandable as a reaction to the near chaos of the previous decade) than it is in the US. Having said that to criticise Russia after fifteen years of a more pluralist polity in comparison to the US seems churlish in the extreme.

But the larger lesson is the implicit problematic aspects of executive Presidency, and we may be moving into a situation where counter-intuitively Russia then pulls towards an executive Prime Ministership. To be honest Prime Minister Putin strikes me as a much more satisfactory state of affairs, even in the context of successive stints in the position. But that leads to other interesting questions. How different would the structure of Russian democracy be, if at all, in such a context. The Presidential model tends towards weaker political parties (something that is evident in both the US and Russian systems). But there is no reason per se why an executive Prime Minister would lead to stronger parties.

It is, however, worth noting that he points to a ‘legitimation’ by United Russia winning the parliamentary poll. I think that this indicates that Putin still looks for some degree of ‘democratic’ legitimation. Sure, like Horne, we can see this as something of a fig leaf, but representation demands popular support. And it is unquestionable that Putin is genuinely very very popular indeed (as Wednesday pointed out on Splintered Sunrise). I’ve noted that his ability to stabilise what was a dismal situation is one part of that, but others are the way in which he and his pulled back key elements of the Russian economy by re-nationalisation. These are innately popular moves. We’ve seen some of the recent international shadowboxing, most entertainingly for those of us of a certain age in the renewed flights of Soviet era bombers (incidentally on KCRW it was pointed out that it was a remarkable achievement in itself to get the TU-95 Bears into the air, since they date back to 1952).

And one can’t help but feel that Putin might understand, or even agree with, Donald Horne when he writes that:

We can avoid being deluded by the magic of democratic ‘myths’: but we can also recognise that legitimating governments is the best we can do. Everything else is worse.

The Czar last time: Yeltsin, Gorbachev and just where did Russia go? April 25, 2007

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Marxism, Russia.4 comments

Strange watching Channel 4 News tonight, and in particular the report from the funeral of Boris Yeltsin. Quite a window on the past it was too with Clinton, George Bush Snr., John Major and other worthies assembled to pay their last respects to the first President of the Russian Federation. Quite a window on the present with those remaining house-trained oligarchs clustered in another group.

And there, also at the funeral one of the pivotal figures of the Twentieth Century, Mikhail Gorbachev, paying his respect to the family and – notably – to some of the current regime members in attendance.

I have mixed feelings about Yeltsin. Actually, no. Not mixed really. Politically it’s difficult not to regard him as an opportunist, a man whose adherence to democratic norms was limited in large extent to the ability of those norms to be of advantage to him. One good thing, his response to the attempts to impose a hard line security solution in the breakaway Baltic Republics led to his call for Soviet troops not to obey illegal orders – unlike Gorbachev, already attempting to maintain his authority in the face of allies who wanted faster reform and opponents who wanted to roll those already in place back, who went remarkably silent for the best part of two weeks. Yet his actions during the 1991 coup against Gorbachev seem to me to be not so much directed by principle but by the possibility that this would finally destroy the power of the Communist Party.

And the famous incident caught in the photograph above following the coup seemed to me to be born of a personal malice rather than a political agenda (although there was that as well). This was a very personal and public humiliation designed to signal the end of the Communist period, but it was also entirely unnecessary. Gorbachev was never the enemy of change, but as an alternate arbiter of it he had to go.

Worse, naturally, was to come. His rule saw Russia enter into a period of chaotic economic change as individuals such as Yegor Gaidar pushed rapid liberalisation of what had been the largest centrally planned economy on the planet. The increase in prices and clear failure of the policies led to the 1993 confrontation with Parliament in an ironic inverse of the earlier coup. And after that? Privatisation, Chechnya and economic instability that was to continue until the end of his rule.

Reading the obituary in the Guardian yesterday, am I alone in thinking that when Jonathan Steele writes that while Yeltsin cannot be blamed alone for the dismal state of Russia in the post-Soviet era ‘Russia needed a more sensitive and intelligent leader during the transition from the politics of one-party control and repression to the politics of negotiation and consensus’ he is thinking of Gorbachev?

Unfortunately the coup plotters in 1992 didn’t merely do in the Soviet Union, they also – by fatally undermining the rapidly diminishing authority of Gorbachev – did in any chance of a managed transition from communist state to democracy. And it’s arguable that without that managed transition the situation we currently see whereby civil society within Russia remains stunted, centralised power remains embedded in the political system and the leadership is drawn from the security forces apparatus, is a result of that earlier ‘original sin’. Putin in power is a worrying prospect. More worrying is the thought that Russia has yet to develop more palatable and popular alternatives (which is in truth a function of the Yeltsin and Putin years), and that some of those on offer at the moment are much less palatable than him.

A couple of years ago I was talking to a member of the Communist Party of Ireland who proposed that Andropov was the man who, had he lived any length of time, would have reformed the Soviet Union unlike Gorbachev who had (according to himself) sold out Communism. I doubt that very much, this being the same Y. Andropov who had been one of those to oversee the Hungarian intervention by the Soviets. No reformist he. No Dubcek, no ‘socialism with a human face’, no Moscow Spring in the early 1980s. But it’s fair to point out that Gorbachev was and remains a convinced leftist and it’s at least possible to argue that had the Soviet Union survived even half a decade more, even in emasculated form, many of the excesses of the Yeltsin era might have been avoided.

But leaving his own words until last it’s worth noting the bitter honesty in what he said on his resignation in 2000 to the Russian people: “I want to beg forgiveness for your dreams that never came true. And also I would like to beg forgiveness not to have justified your hopes.”

The Litvinenko Operation Part 2: The Dublin (or Maynooth) Connection. November 30, 2006

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Espionage, Medical Issues, Russia.3 comments

Clearly the Litvinenko affair has broadened and deepened. Now we discover that radioactive traces – in some cases more than traces have been found on three, perhaps four aircraft. Seemingly numerous locations around London also have similar traces. Meanwhile we now have a Dublin Connection with the strange illness of former First Deputy Prime Minister of Russia Yegor Gaidar. Gaidar was taken ill last Friday at a Russo-Hiberno (if I can coin a phrase) Conference in Maynooth where he was also launching his new book. Journalist Conor O’Clery of the Irish Times detailed on Channel 4 News how Gaidar had become extremely ill during a talk being forced to run from the room where he promptly was violently sick for some time. I think in his overly detailed description O’Clery recounted blood coming from Gaidar’s nose. In any event medical authorities believe that he seems to be suffering from some form of poisoning. A remarkable coincidence in view of the Litvenenko poisoning.

Gaidar is an interesting character. Former Communist turned free market evangelist, in some respects it’s not unfair to see him as the architect of later economic problems due to his extremely liberal reforms in the early 1990s. Since he left power in 1994 he was for a time politically active, albeit in parties of declining significance, but went back to his previous career of researcher.

So what to make of this? Well, rather like Litvinenko, it’s hard to the neutral eye to see Gaidar as an immediate threat to Putin or Russia. Why go to the trouble or effort of transporting radioactive materials hither and yon to remove two rather peripheral players? Why make such a meal of this transport to the point that radiation is left on aircraft. Again on Channel 4 News it was noted that it is relatively easy to contain these substances so there is no leakage.

Unless of course this is deliberately portrayed as a botched job in order to deflect attention away from those responsible. And this is where this tails off into the improbable on all levels. As easy to say that it’s a deliberate ploy to make Putin look bad. How can we judge?

I mentioned (and was perhaps somewhat reasonably taken to task by JCSkinner for appearing unfeeling of Litvinenko’s death which I’m certainly not – it’s tragic for him and his family) previously how this was reminiscent of the Cold War. But in a way it’s not. The Cold War was never this unhinged, never this unpredictable. Yes there was the incident with Mharkov, but that was more remarkable for being atypical than commonplace. Indeed it’s perhaps telling that it was carried out by one of the proxy states in the Warsaw Bloc. Generally speaking Cold War espionage was muted, below the surface and played out with remarkable precision by the competing powers.

This is different, very different.

A final thought on the matter, if a tiny quantity of such radioactive material can cause this level of unease, it’s chastening to consider what those with grander ambitions might do given the opportunity. And gloomily intriguing that it hasn’t happened to date.

Now I’m away to catch up on The State Within, because as I implicitly noted in the earlier post sometimes the comforts of fiction are…well…just more comforting than a real world of radioactive passenger aircraft.