Live again… August 31, 2007

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Uncategorized.add a comment

Yet again one of our number, who goes by the pseudonym of Dónal, has been invited to discuss the Sunday Newspapers on Taste on NewsTalk 106-108fm – hosted by Fionn Davenport Saturday evening sometime after 8.30.

Setting out the electoral stall… Eamon Gilmore and 30 Labour seats… August 31, 2007

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Irish Election 2007, Irish Labour Party, Irish Politics.6 comments

Interesting post by Simon on irishelection who seems to be dubious about Eamon Gilmores opening leadership campaign gambit, the idea that Labour should aim for 30 seats. Easy to say one might think, and a good five years until it was proven one way or another. But I suspect that if Gilmore gains that many he may well have a headache.

But I’ll return to that in a moment. In a way I don’t want to write much about the leadership election (if indeed there will be one with the field narrowing swiftly to E. Gilmore and A.N.Other) so let me throw out a few thoughts about the Party itself.

At the weekend Gilmore proposed that: The Labour Party must “regain confidence in its core values”.

It’s actually not a bad line. Problem is that the sort of permanent modernisation of Labour over the past thirty odd years, something that seems uncannily akin to the Maoist permanent revolution, had obliterated a clear sense of what those core values might actually be.

I was at the merger conference in 1999 in the Rotunda. A strange occasion. Many of my former comrades from DL were wandering around in a dejected fashion. This certainly wasn’t what they had struggled over the best part of a decade for, and I was glad that I had effectively left the party years before. That certainly wasn’t the destination of my political journey.

As Gilmore relates we should look to its achievements, and in fairness they’re not inconsequential:

“More than any other political movement, it was Labour and its allies which drove the modernisation of this State, he added.

“Who modernised the laws on personal freedoms and legalised contraception and divorce?

“Who started equal pay for women and introduced most of our equality legislation? Labour. Who brought in most of our social protections? Labour.” He said it was the labour movement that first thought of social partnership.

“And was it not a Labour finance minister who who brought us the euro and who lowered corporation tax to stimulate investment. The reality is that some of those who now appear as modern celebrities were still cowering from the crozier while Labour was doing battle with conservative forces to make Ireland a modern country.”

Well it may be overegging the pudding, but much of that is more or less true [although is it just me, or doesn’t that read a bit oddly considering he happened to be in a different party all the while?]. How this fits in with the siren voices who talk about reforming Labour, name changes and such like is another issue.I never joined – although believe it or not in the early 2000s I came as close as writing up an application form and trying to work out how much I might donate to the party – because when I looked at Labour I seemed to be seeing not one party, but a multiplicity of parties. Which was the real one? That of Michael D. Higgins, or Declan Bree or indeed Eamon Gilmore? I couldn’t work it out. Was it Labourist, Social Democratic, Democratic Socialist? Any or all of these things?

Clearly it was socially liberal, but was it somewhat too focussed on that, too caught up in one form of the modernising agenda to the exclusion of others? Or was it more socially conservative than often thought? What about economics? A bit more tax and spend than other parties, but in a curious way unconvincingly so. And what about the North? One of the most telling political acts of the 1990s had been the way in which during the Fianna Fáil/Labour government Dick Spring had been seen as the person more sympathetic to Unionism in that administration, and in the subsequent “Rainbow” somehow overnight he became the greener nationalist in contrast to De Rossa and Bruton. That’s a hell of a change whatever way one cuts it.

I’d also always found the vitriol from LP members (not all, but some) about Sinn Féin and Fianna Fáil to be curiously off-putting. Sure, I’d have my political difference with both those organisations. But somehow it all seemed both unpleasantly righteous and also curiously ineffective. It’s like anything, arrogance to be even slightly convincing demands at least some substance and achievement, and with contemporary Labour that simply wasn’t visible.

Quinn was an interesting leader. I’ve already written about Rabbitte, and now the field is full of contenders for the next stint. And this is, of course, the big one. Whoever is leader has to bring Labour back to power because, as has been noted here before otherwise we’re talking about 15 years outside government.

Which brings me to the magical number 30.

30 is achievable. They did it once, they can do it again. But last time out was 1992 and in the context of a weakened Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael. I’m not sure that that set of circumstances will be replicated.

Being completely hard headed about it I suspect that this government will survive intact to the next election. The individual components are locked in tight. They won’t budge – although interesting to see Finian McGrath go on something of a solo run at the weekend.

In that context I think we might see a dynamic of many independent candidates, all eager to replicate the McGrath/Lowry/BCF deals – and some of those may well be disenchanted FF and FG members not given the nod. Of course, independents tend to be self-limiting, the more there are the less influence they wield, but so what, the people will speak.

In that context, as with 2002, it seems to me the likelihood would be a bleed in support from both major parties. It might only be half a dozen seats or it might be more, and note that there will be a process of natural attrition from candidates who hung on for Enda in this last election and FF might lose some as well. No Bertie, perhaps no bounce. But then again, we seem to live in a state where people are nervous about no FF.

Put that together with a dynamic Labour party (that of course is a whole different ball game. Dynamic in what way, pitching to the middle class, or retrenching in the working class, trying to prise away FF seats or FG, or both? Straw in the wind, the rapid jettisoning of the Mullingar Accord since the new government came into office, let’s see if that lasts the next five years) and the chances of them gaining an extra 10 seats are not beyond the bounds of possibility – intriguingly in 1992 DL had four seats and there perhaps 2 more seats that could be counted as ‘left’. This time out a bloody but somewhat unbowed SF will probably pick up two or three more, but that would still leave sufficient space for Labour to expand.

Of course the major fly in that ointment is that they would then probably be unable to go into coalition with FF unless FF was weakened sufficiently because the divvy out of Ministries would be too great. So that route to power is blocked. Fewer seats, a weaker Labour party and then the electoral game comes out more in their favour. So while it makes good political sense in the short term for Gilmore to talk up seat number, in the longer term, perhaps not so wise and cooler heads in Fine Gael might have a story to tell about the pleasures and pain of sitting on 50 plus seats but condemned to opposition for the next five years.

I’m all for Labour gaining 30 and sitting there with allies to provide a genuine ideological opposition. But politicians are human and I wonder how keen they would be to see such a scenario develop, even if it was to see the back of the 2.5 party system (incidentally kudos to Pat Rabbitte for sticking to the Mullingar Accord as long as he did, a bizarre policy but at least it was consistent)?

Of course this is all shooting the breeze at this stage. I could probably make a counter case as easily. But the basic point is that 30 seats is realisable. It’s what you do with them once you get there that’s the question.

Maybe not quite as British as Finchley? Why, it must be Dennis Kennedy and the Cadogan Group. August 30, 2007

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Northern Ireland, Republicans, The North, Unionism.5 comments

One of the less attractive traits, although perhaps one of the most understandable, in politics is wishful thinking, the belief that by stating something it is true. All of us have seen that, particularly on the left. The revolutionary potential of the proletariat, the idea that somehow SF is vanguardist, the inevitable growth of the SP/SWP/WP/etc, etc…

But to my mind the regular missives from Dennis Kennedy fall into that bracket (incidentally I sort of like Kennedy, he’s a crusty fellow who reminds me of a close relative now since departed and I enjoyed his documentary on the South and North some while back where he made some very interesting – if strongly questionable statements about the RoI).

So no surprise that we have a strange article by Kennedy in the Irish Times today. In a lengthy rumination on the nature of Britain and Britishness under the heading “Coming to terms with the British Question” he raises some – well, to be frank, odd questions and makes some uniquely contradictory points.

He starts with:

Why, in the discussion of Britishness and the nationalist threat to the integrity of the UK, does no one mention Northern Ireland?

and continues:

In pondering British identity and the problems of Scotland, of assimilating reluctant minorities, no one refers to the most serious assault by far in recent times on that integrity – a terrorist campaign that led to 3,500 deaths, and which has absorbed vast amounts of British government time and diplomacy in reaching the accommodation we have today.

All very good questions. And yet, the tenor of them is typical Cadogan Group. There was indeed a terrorist campaign, there was indeed murder. Without going the relativist route both campaign and murders have ended, nor was the campaign something in simple isolation but the cause of numerous dynamics within the North, on the island and on these islands.

He suggests, entirely correctly in my opinion, that:

Behind the radical changes implemented in Northern Ireland might seem to lie a realisation that the United Kingdom is not a nation state, and there is no national identity that can be labelled British. The UK should be seen, rather, as partly a historical accident, and partly a convenient political arrangement within which people of varying identities can live together and organise their affairs in a manner that is beneficial to all. People live in it because they were born in it, because political or economic pressures forced them to migrate to it, or just because it suits them. It is pointless to agonise over Britishness – it is sufficient that those who live in the state recognise its legitimacy, respect its laws and join in the political processes of its governance.

But then performs a rhetorical turnabout:

Or were the changes in Northern Ireland just part of the appeasement of terrorism, and further evidence of London’s distancing itself?

Well, what does he think? Let’s put the word appeasement to one side for a second because it bound up in certain meanings which are broadly unhelpful (although is central to the discourse of the ‘nice, not nasty’ self-declared secular Unionism of the Cadogan Group). Yes, it is evidence London’s distancing itself, and someone as sensible as Dennis Kennedy should be well aware of this, and also note that this is an approach (let’s not reify it as a strategy) which has characterised the engagement by Britain with Northern Ireland over the 20th century. Okay, let’s return to appeasement. Yes, no doubt there was an element of hoping to deal with the problem by ceding some demands – that too is characteristic of British politics, as with “killing Home Rule with kindness”. But that is not appeasement, and really, if one concedes that PSF ultimately came to some degree of agreement with the British state as it currently exists then is that appeasement at all?

In a way what seems to come through from this piece is a sort of somewhat unconscious but very real disbelief that there is a distinction between British interests and those of Northern Ireland, and indeed a further cultural distinction between the two. But look, it isn’t Great Britain incorporating Northern Ireland, but instead the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern ireland. This difference isn’t really that subtle, it is suggestive of two specific entities that have a link but are not synonymous. To an Irish Unionist of the 19th century this would not have been impossible to comprehend, but to Ulster Unionism (which curiously was more than happy to jettison three counties to the South despite the Covenant) it has always seemed a more fractious issue). To argue that there is a specific national identity that flows from the UK is unlikely, considering that even a British national identity – and I actually believe there is such a thing – is hard enough to parse out. But he appears to wish to elide the term British with a political construct, the United Kingdom.

This becomes increasingly problematic as the article continues:

It has taken 70 years for some of those lessons to be learned. While Brown urges everyone in the UK to fly the Union flag, its flying in Northern Ireland is restricted because it is seen as divisive.

But what happens in Northern Ireland is apparently irrelevant. The Governance of Britain says symbols help embody a national culture and citizenship, with the Union flag one of the most recognisable, and it wants current rules of flying it on government buildings relaxed. But not in Northern Ireland. There, it says, there are particular sensitivities.

Firstly it is divisive in a divided polity. Secondly, Northern Ireland is not Britain. There are particular sensitivities. This is the problem. And by the by, there are significant problems and sensitivities emerging in Wales and Scotland, within what is broadly termed Britain.

Then the article takes another turn.

The British should learn from the EU. Like the UK, it is an accident of history, the outcome of appalling wars, but it is also a convenient political and economic arrangement for an ever increasing number of Europeans. Its leaders have been foolish in trying to foster a European identity by decreeing a European constitution, anthem, flag and, now, a president – all trappings of the nation state. The EU is not and was never intended to be a nation state, or anything like it. Nor will a European identity ever replace national identities, however contrived.

To my mind absolutely correct.

That does not mean it cannot be an ever closer and sui generis form of union. Its flourishing will depend on its efficiency in satisfying the political, economic, social and security needs of those who live within it, not on everyone waving a blue flag and singing Ode to Joy.

Also correct.

Similarly, the future of the UK will depend more on efficient governance for all, than on banging on about Britishness.

But again with the Britishness… Let’s be clear. There is a British element to Northern Ireland. This is political, cultural, historic. But Northern Ireland remains sui generis within the United Kingdom, and the odd aspect of Kennedy’s argument is that he seems unable to perceive this.

Earlier in the piece he suggests that:

It was the failure of the UK to accommodate and integrate a majority of the Irish into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland after the 1800 Act of Union that ended in the failure of that union. It was the inability of the UK to reconcile the nationalist minority in Northern Ireland to life within the United Kingdom that led to the IRA terrorist campaign.

Very true. So what is the lesson?

Is there nothing to learn from this? Why did the 1801 United Kingdom fail? A factor was the refusal, mainly at the behest of George III, to grant Catholic emancipation immediately. Irish Catholics were expected to identify with a new state which denied them full political rights. Even after emancipation, they found themselves in a state which was avowedly Protestant, where the monarch was head of the Anglican church, and where that was the established church in both England and Ireland. The Governance of Britain, a potted history of the constitutional evolution of the UK, makes no mention of Catholic emancipation.

Hardly surprising. We’re – although I use that ‘we’re’ advisedly and to refer to Nationalism/Republicanism, rather than Catholicism – not on their radar. Never have been.

There were, and are, other strands to Irish nationalism, but few as all pervading as Catholicism. The lesson was not learned after partition in 1921; the new, reduced, UK still had almost half a million Irish Catholics fiercely resentful of their inclusion in that state. By that time republicanism was another factor in Irish nationalism, yet Catholics/Nationalists in Northern Ireland were asked to give their allegiance to a state which was not just a monarchy, but where the trappings of a Protestant monarchy coloured much of the institutional and social life of the country.

Also very true. And I’m fairly convinced that had Stormont been able to act more generously then it is just possible that a dispensation could have been arrived at that would have allowed at least a partial reconciliation with the state as it was then extant by the Catholic/Nationalist minority. But such a reconciliation was as impossible as it was implausible with Unionism as then constituted in the six counties. They could not allow themselves the flexibility to deal with identity and nationality in such a generous fashion for specific historic and political reasons. And let’s be honest. Such a flexibility was in short supply until arguably this very year when the DUP and PSF sat down together in administration.

So there is more than a touch of ‘if only everyone acted reasonably’ to these protestations. I share that feeling, yet I’m fully aware it was unattainable. But hidden within those protestations is another message, one that Kennedy and the Cadogan Group have been pushing for quite some time, that being that all would have been well if Catholic could be reconciled to the NI state and somehow discard their nationalist and Republican political pretensions. Again, perhaps had events unfolded in 1920 onwards in a different way such an outcome might have occurred. The North is far from the only contested territory on the planet and yet compromises have been reached in equally difficult circumstances. Yet, that too is to argue against fact, against the nature and disposition of those involved particularly – but not exclusively – on the Unionist side [and look at the records in PRONI from early Stormont cabinet meetings on various areas to see how the establishment of the polity was quite deliberately structured to exclude], and yet again most crucially to pretend (for that is what is happening) that Nationalism and Republicanism can somehow be diminished to a cultural expression in a way in which Unionism cannot.

Note too that while he mentions terrorist campaigns he is curiously quiet in making any linkage at all between a situation within which “Irish Catholics were denied full political rights” and that subsequent campaign. Nor was it simply an issue of being asked to give allegiance to ”a state which was not just a monarchy…etc, etc..”. The reality of that particular process was a state which in some respects refused to accept allegiance from Catholics, let alone Nationalists. Those few who stuck their head above the parapet saw no reward for their troubles. A cowed people were offered a ‘cold house’. Curiously this equally important element is ignored.

The heart of the issue is that this is not the Irish question, or the British question, but a number of questions overlapping and intermingling that allow for numerous interpretations. Consider the way in which there is no single agreed Marxist view of the North and we begin to see that to try to place this within simplistic frameworks is a futile exercise.

[Incidentally, and I’m being quite serious, while writing this I noticed that the little Irish flag under character input on my Apple menu changed to a Union Jack – now, I wonder how that happened, presumably sufficient inputs of “Britain” or “British” will have that effect!]

The Gardaí, symbolism and secularism… or it may be more difficult than we thought folks! August 29, 2007

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Culture, Ireland, Religion, Secularism, Visual Culture.19 comments

In light of the current debate on the wearing of a Turban I have to ask has anyone looked, and I mean really looked, at the symbolism of the Gardaí. Fintan O’Toole has raised some interesting aspects of the culture of the Gardai, noting that:

The Garda organises Masses to mark the anniversaries of the opening of police stations. The Dublin metropolitan traffic division, for example, holds a Mass in Dublin Castle which has been attended by the President at least once in recent years. The Garda Commissioner, Noel Conroy, attended the Mass in Knock Basilica to mark the beatification of Mother Teresa, of whom, on her death in 1997, the Taoiseach informed the Dáil, “no one doubts the evident saintliness”. Gardaí on duty, like the Taoiseach in the Dáil, wear ashes on their foreheads on Ash Wednesday.

But there is a vastly more basic element of the imagery of the Gardai which might give one pause for thought as regards secularism.

The Garda badge, designed in the early 1920s by John Maxwell, of the Dún Laoghaire technical school and a member of the Gaelic League is an explicitly Celtic Christian device in the general style of the Gaelic Revival. It was commissioned by the first Garda Commissioner Michael Stains who was also in the Gaelic League.

Note the way in which the four decorative circles are positioned at each quadrant emulating the boss of a cross. There is some aspect of a ‘sunburst’ motif, often used on military badges (including the original Oglaigh na hÉireann badge from 1913) in the additional four curvilinear points on the emblem, but there is no way of avoiding the reality that this is to all intents and purposes an emblematic Christian Cross.

This is directly positioned within the aesthetics of the Gaelic Revival which saw emblems such as the GAA and Gaelic League use imagery which has linkages between cultural nationalism and Christian signification.

Is this imagery sufficiently beyond religious signifiers? I’d argue probably not. The visual elements are simply too obviously rooted in that discourse.

Seems to me that we might just have a bigger task than just thinking about the ashes on Ash Wednesday.

I should note that while not a huge fan of Celtic Revival material generally I actually think the Garda badge works pretty well visually. There’s a certain balance to the composition and decorative features that applies to most media or surfaces.

Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, Ed Moloney and the thorny problem of ‘principle’… August 28, 2007

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Ireland, Irish Politics, Northern Ireland, Republicanism, Sinn Féin, The other Sinn Féin.15 comments

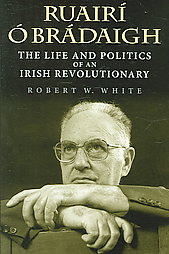

I’m reading Robert White’s book on Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, and I have to admit to finding it both an enjoyable read, a fascinating insight into the genesis (or perhaps more accurately the continuation) of a certain strand of Republicanism – one that would be very different to my own – and essentially a good appraisal of the man and his times. It’s difficult to entirely judge Ó Brádaigh’s character this early into the book, I’ll keep you posted. Certainly it is a book that I’d recommend to anyone interested in the area.

There’s a lot to think about. For instance – and Ó B does critique this in the text – the reification of abstentionism from the national parliament does appear to be at least connected on some level with the political career of his own father, Matt Brady, who was an Independent Republican councillor but never a TD, in his native Longford. I’ve never bought into abstentionism (bar Westminster). It has always seemed to me to be a massive strategic error and one which no principle can really explicate. Why county and not national? Both draw legitimacy from the same legal sources, but more importantly both draw a greater legitimacy from the tacit approbation of the Irish people. One can’t help suspecting that they represent a fetishistic touch stone rather than a considered position – except on one very significant level which is that once inside a national parliament the nature of the engagement by a political force does actually change. Any of us who went through parties who wrestled with attaining that level of representation know that process all too well. So if one wishes to retain integrity, best stay out. But… one can almost be guaranteed of political marginalisation.

One remarkable element that White notes is the incredibly good relations between Ó B’s father and former IRA man, later Fine Gael TD Seán Mac Eoin who delivered the oration at his funeral (and offered a Defence Forces bugler which was accepted by Ó B’s mother on condition that he was not in uniform, a condition that was complied with). Indeed there’s a whole history of how locally FG and Matt Brady voted together on council resolutions to oppose the Treason Bill and the Offences Against the State Act. The real enemy, whatever the rhetoric, was of course Fianna Fáil. Then there is the Border campaign. Now there was a failure, and one that was a failure almost from the off with columns picked up on the same day as incidents and the IRA leadership pulled in shortly thereafter. It kept going, but the lessons learned, or not as rumblings in South Armagh two and a half decades later about ‘flying columns’, seem to have merely added to the belief in an armed campaigns efficacy – any armed campaign. Anyhow, those are discussions for another day.

But, above and beyond this I want to mention the Foreward written by Ed Moloney [I should note that I’ve always liked Moloney’s work, A Secret History of the IRA is a great read]. And what a Foreward it is, since rather than concentrating on the sterling qualities of R Ó B, we are instead treated to a compare and contrast between R Ó B and …er… Gerry Adams.

Moloney contrasts the way in which he was ‘manipulated’ by the Adams camp in 1980 in such a way as to lock him out of communications with the Ó Brádaigh camp. Poor old Danny Morrison is painted in dubious colours… as Moloney says after spending “…many hours together that Summer, often on the road…the article was writen and looking back on that episode it is difficult not to conclude, unhappily, that much of it reflected the direction I was steered towards’. That Kerouac-like interlude was clearly replaced by a Damascene conversion at some point… because as he notes:

“I was able quite easily to confirm the Provisionals were indeed riven at that time with divsion and tension and two camps now existed, one represented by Adams and his young, militantly left-wing northern supporters and the other led by Ruiarí Ó Brádaigh…the older southern-based veterens who had been at the forefront of the first leadership of the Provisionals… suffice it to say that my article oversimplified the dispute to the advantage of the northerners, portraying it as being about left versuis right, young and angry versus old and jaded, revolutionaries versus conservatives, the clever and imaginative versus the dull and gullible. I would not write the same article today…”

Ouch.

According to Moloney, Morrison led the charge to condemn his article at the next Ard Comhairle meeting, and this was evidence of a “classic Adams stratagem, one characterised by its multiple goals and a level of deceit in implementation”.

Now let me stop right here and note that the organisation which Moloney was dealing with was one of the most efficient and ruthless political/paramilitary organisations ever seen in Western Europe. Not the Scouts, not the Jehovah’s Witnesses, not even the Rotarians, but instead a grouping capable of appalling acts of political murder, enormously complex negotiation and political organisation of much of a community.

And the complaint is ‘deceit’?

Moloney though, considers that this is a ‘metaphor’ for the difference between R Ó B and GA and their ‘brands of Irish Republicanism’. And hence why Adams is now leader of a party represented in ‘four parliaments’ while Ó Brádaigh ‘heads a small group…on the margins of Irish politics’.

Adams is characterised as ‘deceiving’, ‘pretending’, ‘breaking the rules’, ‘lying’ ‘lying grotesquely’ and ‘lying routinely’, whereas the ‘ethical difference’ with Ó Brádaigh is one where the latter ‘simply refuses to answer (a question on membership of the IRA)’, ‘played by the rules’, ‘felt obliged to obey AC edicts’, ‘would not tell the full story or would dodge the matter if it suited him’, and these paragons of ethical virtue ‘were the yin and yang of the Provisional movement’.

Yin and yang if one’s definition stretches to some distinction between evasive and deceitful, or sins of ommission and commission.

And the differences are because?

Well, according to Moloney it is because of… location, location, location. Ó Brádaigh ‘could trace ideological roots all the way back to the 1916 Rising…’. Whereas ‘Collins and de Valera were willing to exchange principle for power’ R Ó B ‘came from the uncompromising wing of Republicanism for whom principles were sacred because Republicans had died and suffered for them, in Ó B’s case, his father…’.

Compare and contrast. Compare and contrast.

‘Adams had family ties to all this, but his roots were in the northern IRA, and the northern IRA was always different from the IRA…’. An instance he offers us is the way in which the northern IRA supported (the hated – wbs) Collins during partition because Collins ‘waved a big stick at the Unionist and Protestant establishment in the north and stood up for Catholic Rights’.

Well fancy that.

Northern ‘activists’ are charged with supporting the northern IRA which took the opportunity to ‘strike back violently at the state and people which had for so long discriminated and oppressed their fellow Catholics’.

This thesis is developed further by noting that the Provisionals came in large part from “Defenderism” and sectarian traditions of Irish Republicanism, so unlike those of R Ó B. So this ‘defence’ led to pragmatism, and ultimately the original sin of the ‘peace process’ after which further pragmatism led to accepting the ‘consent principle’ and eventually – although this predates Stormont – government with the DUP.

After which all one can say is, well, perhaps – just perhaps – if one was in Belfast dealing with all that that environment might throw at one in political terms standing up to Unionism and attacking those who had discriminated and oppressed one might just take a bit higher priority than the ‘principle’ of the Republic.

Perhaps too the reality of having to deal with Unionists on a day to day basis gave a certain breadth of vision.

Moloney’s charge is massively contradictory. Those in the north, who the situation most impacted upon, are the very ones who are criticised because they’re from the North. And therefore anything that they were involved in is immediately suspect. It’s a circular argument of breath-taking audacity.

No mention of the shambolic campaign throughout the 1970s or what of the internecine warfare with the Officials on the watch of the southern leadership. No mention of cessations in the 1970s either. No sense that those who had led had some pretty profound failings in the eyes of those they led, particularly those involved at the hard end.

Now, I’m happy to critique the 1980s leadership as I would PIRA, probably in much the same way as I would critique the 1970s leadership. I can understand how violence erupted, but to sustain and expand that level of that violence throughout the 1970s into the 1980s and then on to the 1990s is less understandable. I could condemn out of hand, and it wouldn’t be difficult, but I don’t think that would be useful, nor would it be entirely honest. I don’t want to retreat to a defence centred on my not being there at the time, but… the dynamics within organisations and environments is such that choices are often made and paths taken that in other circumstances wouldn’t have been. That they are often self-sustaining is often not hugely pertinent. They exist.

And here I think is the enormous contradiction at the heart of Moloney’s thesis. Because in a sense it is irrelevant what sort of people R Ó Brádaigh and Adams were. It is what they did that is important. If one took Ó Brádaighs line then there was no compromise, no messy deals, no ‘acceptance’ of the principle of consent. Instead there would be nothing but steadfast allegiance to a tradition that had delivered almost nothing in the years since partition. If one took Adams line then there was compromise, pragmatism, realpolitik and a fundamental reshaping of what it meant to be Republican.

Is principled resistance any less cynical when it assists young men and women to go out to die in a cause that cannot be won than unprincipled pragmatism that eventually stops the killing for an unsatisfactory compromise?

And even if Adams were completely wrong, which he and his might well be, there is nothing in the historical record to suggest that Ó Brádaigh was right, nothing indeed other than the comforts of resistance, abstentionism and an increasing isolation from the Irish people who above all should be central to any Republican project.

The Left Archive: Peoples Democracy, ideology and just what is Trotskyism? August 27, 2007

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Irish Politics, Leninism, Marxism, People's Democracy, Trotskyism.39 comments

This – no, not the image above which is a publication from 1970 – this here cover-2.pdf is fresh from the archives, an interesting document entitled “What is Trotskyism” issued by People’s Democracy in or about 1980. The pamphlet contains a speech by veteran Trotskyist Ernest Mandel (a fascinating person in his own right who seems to have been able to overcome much of the usual tendency on the left to cowerg behind the lines and instead been willing to discuss and argue with political opponents) during a debate with Monty Johnstone of the CPGB from 1969. And it’s a pretty good explication of what Mandel considered was currently existing Trotskyism during that period.

It’s sort of fun. Within the pages there are three images, one of Trotsky, one of Lenin and then a third of a Peoples Democracy March from the late 1960s, perhaps even the PD march at Burntollet. Simply produced by PD on a typewriter. We have ads for their bookshops in Andersonstown and Killester (that well known hotbed of revolutionary activity).

The debate itself is quite interesting. It was clearly at a point when Trotskyism was resurgent, buoyed by the rise of the New Left and student movements. Indeed the spirit of ’68 permeates the pages, particularly when Mandel raises some quite frankly excellent questions regarding the role of the pro-Moscow PCF during May 1968 (although one might suggest that it’s always easier to be complaining about the exercise or non-exercise of power when one has effectively none). And in a fascinating foreshadowing of later and more contemporary debates Mandel argues that the invasion of Czechoslovakia ‘…not only violated the sovereignty and independence of a small nation…but was equally criminal in other respects’. This concentration on sovereignty is quite telling (although to me a bit contradictory for internationalists)… anyhow. Read the rest yourselves!

The ideological basis for this tilt to Trotskyism by PD (which also flirted with Maoism) developed during the 1970s, although it is in a sense hardly surprising that such a political child of 1968 would find other more traditional left formations difficult to align with (indeed there has to be a thesis subject there on the way in which the appropriation by SFWP effectively closed down the option for our homegrown radicals to follow the Moscow – or even really the Havana route). By 1976 they were recognised as the Irish section of the Fourth International.

In a way the longevity of PD is remarkable. From the early days as part of the campaign for civil rights the movement transcended its roots as what appeared to be a fundamentally student based organisation. In the early 1980s they held two seats on Belfast City Council. But as PSF moved towards a more overtly political stance it provided both competitor and new home for some PD activists. Eventually, as late as 1996, it was dissolved and replaced by Socialist Democracy.

Any of you who know the story from the inside I’d be most interested to hear more. It sounds like a remarkable organisation.

Incidentally I can’t resist decoding the cover of the Northern Star from 1970 above. Its got it all, doesn’t it, from Larkin, to a youthful rioter and then a stencilled Starry Plough. Oh yes, and two initials which at that time wouldn’t quite resonate with quite the same chilling effect as more recently!

[Image above from CAIN]

The Bourne Ultimatum – a very contemporary spy movie. August 25, 2007

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Art, Culture, Film and Television, The War On Terror.add a comment

Interesting stuff the contemporary spy movie. Ever since Paul Greengrass got his hands on the first of the Bourne franchise he’s been able to work a certain magic upon what was a rapidly atrophying genre. So much so that we can now forego the nonsense of the last of the Brosnan Bond franchise which saw invisible cars skidding around ice sheets. Two cheers for that at least.

Whether Casino Royale was quite the reinvention some have suggested is a different matter. Good, I thought, but also peculiarly ropy in places, particularly in the final set piece set in Venice where one just knows that the pressure from industry execs to get one big showy finale overcame the more restrained elements that had preceded it.

And perhaps an extra cheer for the current Bourne film which I saw yesterday. There’s lots to admire, even quite a bit to like. The pacing is excellent. Grainy shaky camera work with little or nothing of the glossy high finish and CGI that has come to represent the average Hollywood product. In fact the visual style is not entirely dissimilar to that series of early 1970s thrillers typified by Three Days of the Condor and The Parallax View. Cars crash, colours collide, disaster movie stuff. Again and again and again. From set piece to set piece. First we have a cat and mouse game in Waterloo train station in London between Matt Damon, a Guardian journalist he is trying to assist and a CIA backed assassin. Then there is Madrid. Then there is Tangiers. Then New York. And travel in this series is low level. There is little of the exotica and excitement that characterised the early Bonds, where it was possible for the audience to live somewhat vicariously through the lead… in Bermuda, or the wealthy resorts on the south coast of France. Bourne uses ferries, trains and suchlike, to the point one wonders about just how low impact is his carbon footprint. The locations are the underground car parks and service corridors that one sees bizarrely in the West Wing when the President is decanted from a limousine in the access ways leading to restaurants and suchlike.

But then, and this is the real strength of the film, this is juxtaposed with a contemporary communications and surveillance system that has a terrifying authenticity to it. Mobiles are tapped in real time. Offices bugged. Surveillance cameras co-opted to target individuals. Banks prevented from making payments and so on.

And Paul Greengrass uses the skills he developed as a documentary film maker well. At times the action unfolds like a sort of meta-lesson in just how security services operate, for good bad and exceedingly ugly. The film is littered with references to the war on terror. Hooded captives. Renditions. Termination of agents. Experiments in de-personalisation. And even the suggestion of deep cover assets used by the CIA who may not even know which side they work for.

Matt Damon, for slightly too long rather unwinningly youthful in the role suddenly – finally – begins to look his age, and none the worse for it.

One criticism is that women fare poorly in this series. That’s true to a point. The rather fantastic Franka Potente was killed off in the first five minutes of the second movie. Julia Stiles is fairly reserved in this movie. Yet Sarah Churchwell who wrote an argument about this in the Guardian recently neglects to mention the moral centre at the heart of the film in the form of Joan Allen as CIA boss Pamela Landy. It is her energy and autonomy that carries the plot forward throughout to the closing minutes [incidentally, and on a slight tangent, I caught five minutes of Wolf Creek last night on RTÉ 2. Now that’s misogynistic. I hope I never catch another five].

Another might be that the Guardian comes out both with reputation as fearless purveyor of truth enhanced but with its journalistic staff portrayed as idiots unable to keep their heads in a life-threatening situation.

But these issues don’t detract too much from the film. Indeed it is heartening to see that it retains at its core some of the humanism that characterised the original source, the thrillers written by Robert Ludlum. They were never great literature. But at the height of the cold war they were quite unusual in recognising both the cynicism of the links between east and west and the inherent humanity of those involved in such activities. And the original Bourne novels were explicit in blaming an intelligence complex that was largely out of control.

Greengrass presents a Bourne that resonates with contemporary issues. But in a way the issues are no different in real terms than they ever were. An interesting, instructive and entertaining film.

Race and Ireland. An incident in Limerick in 1979… August 24, 2007

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Ireland, Society, Uncategorized.21 comments

While we’re still digesting the news about P. Rabbitte, thought I’d throw this out. I was watching Siar sna Seachtóidí on TG4 [and on my internet browser the fada’s don’t come up properly, which is odd for what is presumably and primarily an Irish language website] some weeks back, which covered news stories from 1970s. The year was 1979. Fabulous stuff. Happy Man was the entry in the Eurovision, a song that managed to marry Neil Diamond and Abba in a toothgrinding combination. Gay Byrne flirted with the Rose of Tralee. Princess Grace of Monaco, Irish/French accent in tow, opened the Theater Festival.

20,000 people marched in the Wood Quay protests but the diggers went in anyway. Hundreds of thousands marched in the PAYE Tax protests, and nothing was done about it. Jack Lynch resigned as Taoiseach.

Watching the footage it wasn’t hard to believe that Ireland was in some small way a sort of cousin of the Eastern bloc. Everything was drab browns and grey. The news reports filled with shiny mens suits and flammable looking womens dresses.

But in amidst all that was a remarkable, and troubling, story about four Nigerian students in NIHE in Limerick who were refused entry to the Savoy venue in the city.

The students said that they were told blacks weren’t allowed in.

When the media caught hold of the story the excuses provided by the management ranged from the absurd, “…other students had used foul language…” to the pathetic… “confusion over pricing” and finally “…the venue was full and because they were in the overspill they weren’t allowed in”.

Planxty, who had been booked to play the Savoy a couple of nights later, cancelled their gig and moved it to NIHE in solidarity with the students, and a petition was organised in the college.

A small incident. But revealing for the range of responses both good and bad. Does anyone remember anything further about it? Were there any repercussions?

Collateral damage: The latest casualty of the Mullingar Accord… Pat Rabbitte resigns August 23, 2007

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Irish Election 2007, Irish Labour Party, Irish Politics.13 comments

So, the political catastrophe for Labour that was the Mullingar Accord continues to work its dark magic. First it skewers the Labour Party in the General Election, now it fells Pat Rabbitte.

I have two reasons to thank Pat Rabbitte for assistance he gave me over the years. So while politically I fear his tenure will be seen as a period of retrogression for the Labour party I still wish him well. But I am convinced that his leadership was, if not quite a disaster for Labour, one of the most pointless interludes in that party’s existence.

A strange time to choose and in a way an unusual man. Clearly very clever, but with almost completely the wrong personality for the job at hand as leader. The conference this afternoon seemed to typify that. The references to ‘regime change’, ‘a party more united than it had been since 1922’ and such like seemed a tad too glib. He told us he ‘gave it his best shot during the election but he failed’… Well, yes.

He reminds me of other examples of clever men who arrived in positions of leadership in various political parties, one thinks of Alan Dukes, etc, etc. Each personally clever, indeed in some cases brilliant, but each lacking some intuitive capacity to connect with either his own base or the general electorate. And that former problem is as important, if not more, than the latter. Knowing people in Labour I was struck by the bitterness of those who might be termed ‘old’ Labour to the new arrivals from DL who had carried out a reverse take-over of the higher reaches of the party structure in the early 2000s. I’m used to political bitterness, the circles I was in thrived in it. Come to think of it they still do.

In a way what was most striking about his leadership was the almost complete avoidance of a defining ideology. For a man who had come from one ferociously ideological party, and been a member of another which was reasonably clearly defined there was no sense that he had any vision which linked into a broader sense of what it was to be ‘left’ in this society. But why is this such a puzzle. Even in the WP I never had any feeling that Rabbitte was an ideologue. His popularity with the media seemed always to be a function of his closeness to journalists down at Doheny’s. Never the best constituency upon which to base a judgement of broader popularity. Although he was a pleasant man in such company, being both witty and quite generous. This personal warmth never translated to the larger canvas of the Dáil chamber or the party conference. Indeed in these contexts a certain autocratic aspect, whether true or not, seemed to be evident.

Add to that a career littered with the extravagant, the exaggerated, the simply incorrect (who now remembers about the documents that would – and I paraphrase – ‘shake this state to its very foundations’?) was one which quite frankly should have given Labour pause for thought when they elected him leader. Because that style, born of student politics but clearly impossible to transfer to the more staid world of party leadership in this democracy, was not what was going to be presented the electorate.

And it wasn’t. Instead we had Rabbitte the rather dull. Not bad by any means. Just nit-picking. Hesitant to strike, hesitant to withdraw, and in that respect more similar to Enda Kenny than some might imagine (albeit without Kenny’s clear ability to organise, an ability that probably secures him the leadership of FG for a number of years yet – although who knows?). That first little contretemps regarding the Ahern finances said it all. The aggressive politician of yesteryear unwilling or unable to risk a throw of the dice (a la Dick Spring in the early 1990s) for fear of what? Losing the mantle of sober gravitas – something Irish politicians seem to think in and of itself is sufficient preparation for government? It’s not guys, because it’s so transparetn. Eventually that left the sense that this was a version of the Labour party that was averse to any risk taking at all.

The egregious errors that he made as leader now seem almost incomprehensible. The oddity of taxation policy, making gestures that simply didn’t resonate with the public (or worse alienated parts of the party support). The inability to publicly countenance coalition with Fianna Fáil. Great, in theory, if one wishes ideological purity. But an awful awful strategy for a group of politicians looking at the wrong side of 50 with no clear alternative route to power. And awful awful too for anyone who wanted even a hint of social democracy added to the political mix over the next five years. And not just an inability to countenance it, because soundings I took with people I knew in Labour indicated to me that there was, and I have to be honest, a hugely cynical agenda that if the nod came Labour would make a deal with the evil ones.

Which made the retention of the Mullingar Accord up until the vote for the Taoiseach all the more inexplicable, since it thereby allowed those seeming neophyte Greens the opportunity to race ahead of their larger and older rival and place their feet firmly under the Ministerial tables. And look, I still suspect that one Bertie Ahern would, given the opportunity, have much preferred to do a single deal with Labour than multiple deals with Independents and the PDs and GP had it presented itself to him. The faces of Labour in the subsequent time period as the reality of a relatively solid Fianna Fáil government sank in told its own story. Lashed in the public mind to a Fine Gael that was resurgent within itself but still unable to connect more widely the slight nod to Sinn Féin perhaps indicates that there is a recognition that the centre ground is perhaps a little too crowded for the party.

So no agenda, no ideology, no clear path forward. If anything just a sort of muffled complaint against an Ireland that had ‘changed’ in some remarkable fashion, particularly and specifically in relation to leaving Labour the also ran – except it hasn’t. Ireland has over the best part of a century taken a look at the Labour Party, and bar one shining moment in 1992 it’s hasn’t particularly liked what it has seen. Now, one can take away a number of lessons from that. One might be that Fianna Fáil remains the predominant ‘workers’ party. Another that ideology is of little interest to the Irish people. A third might be that the left is better served by a number of competitive formations than ‘one smallish party’. A fourth that Labour has never seemed particularly serious about taking any measure of state power except with Fine Gael. And so on.

I can’t state this enough. If anything this is a vastly more social democratic society than it used to be – particularly in the 1980s, but terrifyingly that has little enough to do with the Labour Party. We’re more social democratic (and I mean this in the sense that civic society is vastly more complex, that benefits have been extended and so on) because we’ve been able to afford it and Fianna Fáil remains hostage in no small part to its own populism, but if things go sour, well then perhaps some who haven’t had the pleasure may have a chance to experience 1983, and those of us who did will have the chance to relive it all over again). And part of that process will be an FF which willingly talks populist and acts centre right.

But for FF to act even half way decently it is necessary to have a left which is confident of being a left. With Labour, whatever the evident sincerity of those involved this seems strangely unfocussed.

And Rabbitte’s talk this afternoon begins to seem strangely in keeping with this. Vague talk about a need to change, a need to relate to Irish society. But in what way? The wild mutterings about name changes seem of a piece with this too. Now it has to be said that some of these mutterings appear to come from beyond the party itself, but even so.

This is a society that on a profound level requires some alternative vision of the future, some sense that the nostrums of the right and the market are not uncontested,

But what next? More of the same? Can they afford that? And in fairness to Rabbitte I look at the selection of potential contenders and it strikes me that for all his faults there’s not one that I could say with all honesty had he or she been there for the last five years they would have done better.

Could anyone? Will anyone?

This Ireland… 2 August 22, 2007

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Ireland.4 comments

According to Mary Fitzgerald in yesterday’s Irish Times the Bank of Ireland has changed its latest TV advertising campaign after a customer complained a “bogeyman” character featured in the advert shared his name.

The 30-second advert for mortgage advice initially showed a spiky-eared, furry-skinned “bogeyman” named Derek Whelan hiding under an unsuspecting child’s bed because he and his wife need a bigger place to live.

Funny.

The real-life Mr Whelan, a long-standing business customer with Bank of Ireland, contacted the bank to complain about being linked with the character.

Ooops.

“He contacted us and asked if we could change the ad,” a Bank of Ireland spokesman said.

Okay.

The advert was edited soon after the complaint was made. The character is now referred to as “Dave the Bogeyman”. The advert, the second of three aimed at Irish TV viewers, was first broadcast last week and ran for several days before it was changed.

Problem solved.

Created by advertising agency Irish International BBDO, it features animation by Glassworks, an award-winning company in London.

The Bank of Ireland spokesman said that while commonly used names were given to characters in the advert, there was no intention to identify anyone.

The bank has now decided to use only first names for the final advert in the series.

Probably for the best.

Still, once upon a time people were sort of able to make the distinction between reality and advertising, particularly if that advertising concerned a spiky-eared, furry-skinned creature lurking under a bed.

And what exactly does Derek Whelan, BoI customer, look like?