Atomic Rockets June 21, 2014

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Culture, Science, Science Fiction.2 comments

…a site to lose oneself in if science and science fiction are your thing.

Let’s go back to mine and drink until we can’t feel our legs! Utopia December 7, 2013

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Culture, Science Fiction, Uncategorized.7 comments

Just finished watching Channel 4’s Utopia on DVD, and very good it was too, so good in fact that both the premise, execution and conclusion managed (mostly) to put a new enough twist on that hoary old genre of genetic engineering. Stylish, sure, and studied in its stylishness. Hard hearted to the point of being at times near enough unable to watch scenes of murder, torture, a series of killings in a school (all off camera but violence that didn’t pretend it wasn’t violence). And some genuinely clever plot twists, reversals and character development. Two or three very big plot holes which I won’t mention for fear of spoiling it for others, but recommended. Not least because we get to see Stephen Rea, Fiona O’Shaughnessy and James Fox.

A second series has been commissioned and I hope they manage to stay true to the first one. The last time I enjoyed new TV was BBC’s The Hour, the first series of which was great, but the second, despite excellent performances from Anna Chancellor and Peter Capaldi, wasn’t anywhere near as good as the first.

As indeed was the soundtrack and in particular the theme music by Cristobal Tapia de Veer, with a none more dubstep (and creepy) approach:

Soviet juvenile SF films from the 1970s November 23, 2013

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Culture, Science Fiction, Uncategorized.12 comments

Here’s a real oddity, a Soviet juvenile SF film from the early 1970s, Moscow-Cassiopeia, that is clearly influenced by 2001: A Space Odyssey… at least in the sets and in some of the visuals. Padded walls (that’s not a joke, or is it?), psychedelic lighting effects that Warhol and the Factory would have approved of, they’re all here, though the spaceship isn’t much cop. And that star map on a transparent plastic sheet you’ll see in one of the clips is very 1950s. And as if that’s not enough, the first clip shows clips from both that and from another Soviet film, ‘Teenagers in Space’ as well.

You’ll find Moscow-Cassiopeia in all it’s glory in full on Youtube, not sure about Teenagers in Space (which might be a sequel to M-C, now I think about it).

Marooned! July 20, 2013

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Culture, Science, Science Fiction.5 comments

Actually, what of this from a decade or so after that Men Into Space episode in the previous post. This was a US film that depicts a US rescue mission sent out to assist an Apollo craft that gets into trouble. From 1969 it had an all star cast. And, almost needless to say, who turns up, but the Soviets?

There’s some teeth-grinding sexism in the title caption as regards ‘The Astronauts Wives’. I wonder what Sally Ride et al would make of that.

There’s also Robert Altman’s film, Countdown, released a year earlier depicting the lunar programme and another Soviet angle. Sadly no trailer I can find for it.

Men Into Space! July 20, 2013

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Culture, Science, Science Fiction.add a comment

I’m indebted to Odyssey, e-magazine of the British Interplanetary Society, for pointing me towards this…

Men Into Space, an US tv show from 1959 and 1960. It ran for one season of about 38 episodes and depicted a US lunar exploration programme. It’s a bit workaday, but with some creative assistance from the likes of Chesley Bonestall it was a bit better than might be expected. Still, a world between it and Star Trek which appeared only seven or so years later. Star Trek had its problems, but a cursory look at the MIS episode ‘First Woman in Space’ is no fun for those of us who are feminists. It’s like, well… another world.

I’d never heard of it, not a whisper, before now, and it’s fascinating in its own way. Apparently it took great pride in its scientific accuracy. The above episode deals with Soviet and US missions to Mars where something goes wrong and… well… I won’t spoil it for you. Note that the Soviets have much more futuristic outfits. Not sure what that’s telling us.

Fringe, parallel universes and me… and the other me, and the other me… June 26, 2011

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Culture, Science, Science Fiction.26 comments

A big shout out to Starkadder for directing me to the invaluable i09 overview of the first two seasons of Fringe. And allow me, if you will, an unashamed dip into fannish enthusiasm.

I’ve been watching the series ever since. Avidly. Probably I haven’t enjoyed an SF TV series so much in years – possibly not since Buffy and before that Babylon 5.

And sure, I get the appeal of True Blood, and Battlestar Galactica, but somehow…

I’m not entirely sure why I like it so much. Perhaps it is that it has eschewed much of the hokey stuff that littered the X-Files, perhaps because it has the airy competence and finish which seems to be so typical of much of contemporary US TV, perhaps because on some level it is simply likable in terms of characters and plots. One aspect of it that has surprised me is that I’ve enjoyed the more horror led plots, and I’m usually not a fan of the latter area.

Now, it’s not perfect either. There are a few inconsistencies, and as with anything from J.J. Abrams there’s a sense that when it eventually winds to its conclusion – and yes, it’s been renewed for a fourth season, so it’s looking good – some issues won’t be explained at all. Observers? Zerstörung durch Fortschritte der Technologie? And so on… Expect hanging threads – I mean was it really the wish of a certain character to be validated by one William Bell that drove Season One? Really?

Be that as it may, and spoiler alert approaching for anyone who hasn’t seen it, but the central conceit is one which has very slightly troubled me.

The very concept of parallel universes is one which slips in and out of vogue in contemporary science, though it’s long been a trope of science fiction – blame Murray Leinster if you will for one of the first near modern stories explicitly about same. Or blame earlier writers who managed to think up the idea.

Anyhow last time I checked in some years back it seemed that theory saw it as less rather than more likely. Which was disappointing and when Fringe wheeled around I was like… well, brilliant, but…

But I’d clearly not been keeping up with more recent thinking on the matter, because in New Scientist in recent articles, one from this June and one from last August it would appear that current models allow for parallel universes with little or no problem. In the first piece Justin Mullins notes that

… [researchers] Bousso and Susskind have also linked the idea of a multiverse of causal patches to something known as the “many worlds” interpretation of quantum mechanics, which was developed in the 1950s and 60s but has only become popular in the last 10 years or so.

…and that…

‘when a superposition of states occurs, the cosmos splits into multiple parallel but otherwise identical universes. In one universe we might see [Schrödinger’s] cat survive and in another we might see it die. This results in an infinite number of parallel universes in which every conceivable outcome of every event actually happens.’

Excellent. Quite excellent. I’m probably more pleased than most at this prospect, because I’ve always enjoyed alternate history and parallel universe stories as a specific subset of SF (though there are those who mutter darkly that many of these aren’t actually SF at all). Now mind you I’ve found a certain H. Turtledove’s works a little wordy – though his take on a world where the Nazi’s had won [natch] and a small number of Jews survived inside Third Reich Berlin was pretty fascinating though in the hands of a more subtle author…

Naturally these are theoretical constructs. But they’re ones where the very concept of parallel universes aren’t merely add-ons which are used to illustrate concepts, but may be intrinsic to the very existence of our own universe. Hmmm… all very Fringe.

This leads further. What then might be the possibilities of engaging with such universes? And beyond that what about traveling to them? In an odd way I’m moving towards the position that that might be fundamentally easier than interstellar sublight travel (and don’t get me started on FTL).

Which reminds me of Frederik Pohl’s brilliantly acerbic, and entertainingly political, The Coming of the Quantum Cats which suggested that were it possible to travel between universes that might be far from an unalloyed good. Well hey, I knew that when I read Michael P. Kube-McDowell’s Alternities. And… and… and…

Moon: Landing July 22, 2009

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Moon, Science, Science Fiction.8 comments

Swiftly moving beyond Garibaldy’s poor cultural experience with Moon…

It’s odd looking at the images of the proposed Orion and Altair vehicles that are intended to return the US to the Moon sometime in the next decade as part of the Constellation programme. They’re obviously very similar to the Apollo era modules, a result of a decision to take tried and tested technologies rather than attempt to push the envelope as was seen with the Space Shuttle. These are space going vehicles, rather than Low Earth Orbit vehicles. They can eschew the rudimentary wings, fin and control surfaces of the Shuttle.

And yet, for all the sleek computer animated simulations of the return – and as an aside can one think of any better way to leech the meaning from this than essentially staging it ahead of time in virtual form – they seem strangely lacking.

Okay, I have to admit, Orion isn’t bad. As Apollo writ large it has a clunky retro charm. The interior arrangement, now set up to carry… gasp… four to six astronauts… is more of the same. That flattened cone like shape has the necessary echoes of the past. No complaints there.

Reading the specs on wiki I had to smile…

* “Glass cockpit” digital control systems derived from that of the Boeing 787.[8]

* An “autodock” feature, like those of Russian Progress spacecraft and the European Automated Transfer Vehicle, with provision for the flight crew to take over in an emergency. Previous American spacecraft (Gemini, Apollo, and shuttle) have all required manual piloting for docking.

* Improved waste-management facilities, with a miniature camping-style toilet and the unisex “relief tube” used on the space shuttle (whose system was based on that used on Skylab) and the International Space Station (based on the Soyuz, Salyut, and Mir systems). This eliminates the use of the much-hated plastic “Apollo bags” used by the Apollo crews.

* A nitrogen/oxygen (N2/O2) mixed atmosphere at either sea level (101.3 kPa/14.69 psi) or slightly reduced (55.2 to 70.3 kPa/8.01 to 10.20 psi) pressure.

* Much more advanced computers than on previous manned spacecraft.

It’s like a car brochure… right down to the ‘combination of parachutes and airbags for capsule recovery’… well, okay. Not quite like a car brochure. I’ve yet to see a car with airbags on the exterior.

No, for me the disappointment is the Altair vehicle. Where is the spidery wonder of the Lunar Module? This looks like an articulated lorry in comparision, or no – a container on an lorry. It’s all propellent and payload, a squat utilitarian beast oddly truncated.

I want that spidery wonder back. And I want it now.

And that reminds me of, perhaps, one of the worst Science Fiction movies ever made, the peerless Moon Zero Two, straight from Hammer Films. It appeared a little after the first moon landing and it had a plot that could charitably be called not great. Yet, there was one feature in it that I really really like when I saw it first. And no, it wasn’t the kitsch near genius of its title music but instead a sort of souped up LM that was used to ferry people around the Moon. And this… this was logical. Take the existing LM and add on a new intermediate section.

Of course in reality the legs would have had to be strengthened, the body broadened, and really, was that the best way of doing it? Yet it made sense. Again a tried and tested technology that could be refashioned for years later. Funny thing is that even at the time I wondered whether such technology, or rather its lineal descendent would still be working so many decades later. Surely the design might have changed a tad.

But, when one looks at the specs for Orion and their similarity to the first effort to reach the Moon perhaps I was unduly pessmistic, although note that MZ2 was set in 2021. Now, if only they’d implement a Moon Zero Two LM… then we could truly say we’d gone full circle.

Here, meanwhile, is a clip from Moon Zero Two showing what we didn’t achieve.

And here is the theme music…

A classic of its kind, I’m sure you’ll agree.

By the way, a fantastic interview on National Public Radio’s To The Point this week with Buzz Aldrin about the first moon landing and why humans should go to Mars (he dismisses the Moon as a cul-de-sac). His main reason? If the US doesn’t the Russians and the Chinese will. It was funny to hear such unvarnished Cold War US Nationalist rhetoric, and yet, and yet. There was part of me suspecting that this was only the public reason he gave in an effort to pressurise the US administration. I say that because the sheer sense of wonder at what he had done and where he had gone was still remarkably strong in his recollections. Yeah, I think he got the space bug.

Equally good was a discussion with astronomer Jonathan McDowell and Steven Weinberg physicist about the merits or otherwise of human spaceflight. McDowell and Weinberg differed on that issue to some extent with Weinberg taking the view that unmanned probes can do all that humans can and more, whereas McDowell believes a human presence in some form is essential. Well worth a listen.

It’s available as a free podcast here and on the iTunes Store.

Moon:Memory July 21, 2009

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Astronomy, Culture, Moon, Science, Science Fiction.11 comments

I think I saw the moon landings. I have a memory, I’ve had it for years now, of being in the sitting room of my parents house in Raheny watching the shaky footage on a black and white television. There’s a problem though. It was only this month that I realised that I would have to have been about 3 years and 8 months old when the moon landing occurred. And, given that, is it really likely that I actually saw Armstrong climb down from the Lunar Module onto the surface of the Moon? Or rather that I remembered it? It gets worse. I don’t know if RTÉ carried the footage, but, the time, 3.39 a.m. Does it seem reasonable that I’d have been awake at that point? Maybe I was bundled downstairs to watch. I don’t know and there’s no one to ask. So… the question remains did I see the reports the next day, or did I imagine them happening subsequently.

I suspect the latter two options are most likely, albeit they’re the most prosaic. Ah well. Another option is that I saw subsequent moon landings. It’s funny though. Almost the entirety of my life, including my adult life I’ve been convinced I did see them. And now… I don’t know.

If I did see it I wonder what I thought about it at the time.

There’s a fabulous book that I’ve been reading recently called The Baby in the Mirror by child psychologist Charles Fernyhough which through his appraisal of his own daughters mental development in her first three or four years gives an insight into memory and its centrality to our ability to understand the world.

As he notes:

In contemplating a forthcoming journey, we don’t just make a physical connection with the human being who will be passing through that airport and hailing that taxi; we make a mental connection, imagining the sights and sounds, the varied emotions of arrival. It takes a leap of imagination before we make the leap of substance.

In foreseeing herself in Australia, Athena [his daughter who was going to Australia with him to live] needed some of that self-thread. There was that little person, in the image of the future she had conjured up; there was something that it was like to that little person; and it would be the same as what it was like to be this little person.

Athena needed some understanding of herself as a centre of experience that persisted like her body persisted, with a future as well as a present. She needed to be a time-traveller.

I wonder about that. I was a bit older than Athena, but the way in which events at a very early stage in life impress makes me wonder how much of my personality was shaped by the background noise that was the space programme, something that ultimately fed and informed my cultural tastes, my sense of self. Did the moon landing operate on a subtly similar level with thousands of children thinking that they too could place themselves in the picture, so to speak. That the adventure of it was a visceral part of them and their self-identity, and was this because in large part we were there ready to be shaped just as these events were happening? Otherwise why, if my memory of watching the landing on television is a construct did I want it to be something that I lived through directly?

The meaning of it all is fascinating too. I mean, what did I think was going on then? Fernyhough argues that:

Ask a child, as Piaget did, who made the sun and the moon and you are likely to get a creationist answer. For children growing up on the shores of Lake Geneva, the stars of the constellation of Pleiades might have been scattered there by God. Piaget’s interpretation was that young children suffered from an ‘artificialist’ bias, mistakenly inclined to see a creative agency in inanimate objects. As their thinking becomes flexible enough to give them a basic grasp of the laws of physics, they become better able to see how the landmarks of nature could have arisen without human or divine intervention. Piaget saw artificialism… as a wrinkle of cognitive immaturity which is ironed out by further development. As you grow into more sophisticated reasoning about the physical world, he argued, you rely less on God for your cosmology.

However, Fernyhough believes that this is purely cultural rather than cognitive…

In one recent study, Australian and British children were tested on their knowledge of cosmology, such as their understanding that the earth is a sphere on which people can live without falling off. Even controllling for general intelligence, the Australian kids showed a significantly richer and more scientific understanding of cosmology than their British peers. One might say that they could not help but do so. Australian children grow up well aware of their distinctive location (relative to other English speaking nations) below the Equator. Their allegiance to the Southern Cross, as depicted on their flag, is emphasized in their elementary school curriculum, which introduces cosmology at an earlier age than in the UK.

So perhaps all those news reports and diagrams rubbed off, giving a sense of the universe, or at least the position of humans within it a greater depth than might otherwise have occurred.

Subsequently the memory faded into what I’d describe as a general fascination (although that’s too pointed a term, perhaps interest or even good-will better describes it) towards all things space related. It might have been happening in the sky, on the moon, tens and thousands of miles away, but it was an extension of the 5 year old, 10 year, 20 year old and so on, me. Each achievement, each milestone something to do with me. Certainly that was true up to late adolescence. Skylab fell? It fell on me, metaphorically. I still remember discussing the landing of the first Shuttle with others with that sense of fascination. But something changed. Probably I just got older. Social activities filled in and crowded out that space.

I didn’t follow the programme with the same interest as the years progressed. The news that they’d discovered exo-solar planets through telescopes came as a signficant surprise to me and as the numbers ramped up of just how many were discovered it was clear I’d completely lost touch.

Sure, on the cultural side the consumption of SF in whatever form continued, but the linkage to the actuality of space exploration certainly dimmed. That’s changed. The rise of the internet has made it much more a part of life again. Not in the same way though. It’s not as close, even if I still feel that same sense of good-will towards it. Maybe even a greater fascination as I realise that many of the achievement I once thought would have occurred by now haven’t and may not yet in my life-time, making that which did happen doubly precious (and apologies for the shameless solipsism of this piece… but, thems the breaks)…

But then, how could it be the same? The truth is I’m pretty sure now it didn’t quite happen the way I thought it did… That while it happened, it didn’t quite happen to me…

Moon: It’s scary out there July 19, 2009

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Culture, Moon, Science Fiction, Television Shows, Uncategorized.12 comments

Well, as noted by Craig, this looks at least a little bit impressive.

I’ve got to admit I’m a sucker for anything with model work instead of CGI. I’ll watch old episodes of Space:1999 or UFO to see the vehicles the future was meant to bring us. That it didn’t remains something of a disappointment. So the sight of those faux-2001 styled moon rovers, all chunky angles, strong sans serif typefaces on interiors and exteriors is a joy. This is the future as conceived in 1970 or so and carried through to films like Silent Running.

Or indeed Space:1999.

I’ve already mentioned how, as a kid, I was fascinated by this book. which also had something of that. And the model work was a large part of it. Anderson, Derek Meddings and others through their creations seemed to open a door to the future. This was what it would be like. The very weight of those models seemed to give them a three dimensional aspect, a reality as it were, that computer generated imagery couldn’t. The sheen of CGI, while often in its own terms fascinating, just isn’t quite there. Even now.

Now granted, some of this presented a very pristine vision of the future. But that of Anderson wasn’t, or at least wasn’t entirely. The vehicles in UFO could be grubby, their sides scored by rocket exhausts and such like.

That thought in mind I was looking up some of that on YouTube recently and came across both the UFO opening credits and the end titles.

Here’s the opening credits, all 1970s poppy excess as if it were the Avengers.

And here, by way of contrast, are the end titles.

There’s something undeniably eerie about the way the camera pulls back from the Earth with that score, by Barry Gray, in the background. It’s sort of the flip side of 2001. Whatever is out there may not be pleasant at all.

As a commenter said on YouTube:

What a contrast with the jolly and forthright “Lets go get ’em!” opening theme. When I was a kid watching this show the end theme seemed to say “we don’t stand a chance gainst the aliens”.

We don’t stand a chance. Yep.

An oddity though. Is that the Moon behind the Earth, and if so then what precisely is that planet or moon that the camera finally reveals?

Kilbarrack, 1973 and the World of Tomorrow… December 7, 2008

Posted by WorldbyStorm in Culture, Science, Science Fiction, The Left.34 comments

Get your ticket to that wheel in space

While there’s time

The fix is in

You’ll be a witness to that game of chance in the sky

You know we’ve got to win

Here at home we’ll play in the city

Powered by the sun

Perfect weather for a streamlined world

There’ll be spandex jackets one for everyone

What a beautiful world this will be

What a glorious time to be free

I G Y – Donald Fagan.

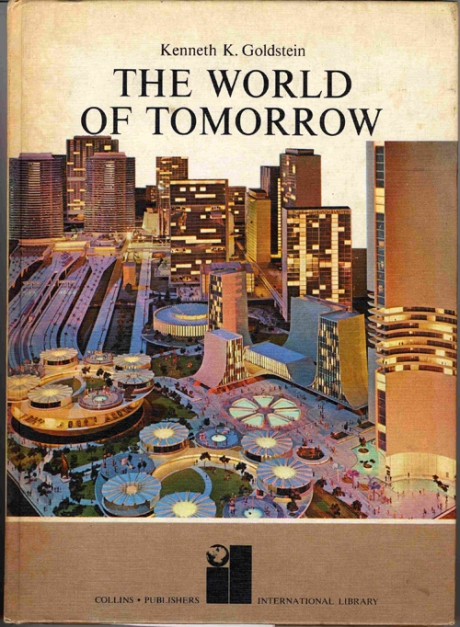

When I was seven, or perhaps eight, I found a book in the Library of Scoil Lorcáin National School in Kilbarrack. All told it was a pretty good library with a fairly large selection of books. Even today I can remember many of the volumes that were there – a book about BOAC passenger aircraft which had silver Constellations and Viscounts set against improbably azure skies, another about Russian Fairy Tales with strong expressionistic illustrations that simultaneously were attractive and terrifying, another on Irish history with muddy watercolour paintings of round towers and crannógs. But the book which has stayed with me most was a volume entitled The World of Tomorrow. Written by Kenneth Goldstein in the late 1960s it sought to describe developments in technology, science and society in the future.

I can’t quite work out was it the book which sparked my interest in all things futurological or did the interest come earlier? My Dad had had a small selection of science fiction titles he had picked up in the late 60s or early 1970s. I studied the covers first and then later read them. Jack Vance’s superlative The Dying Earth, Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End. There were others, an Asimov or two… but I don’t remember all of them. And I can’t work out the chronology accurately. I think the books came after The World of Tomorrow.

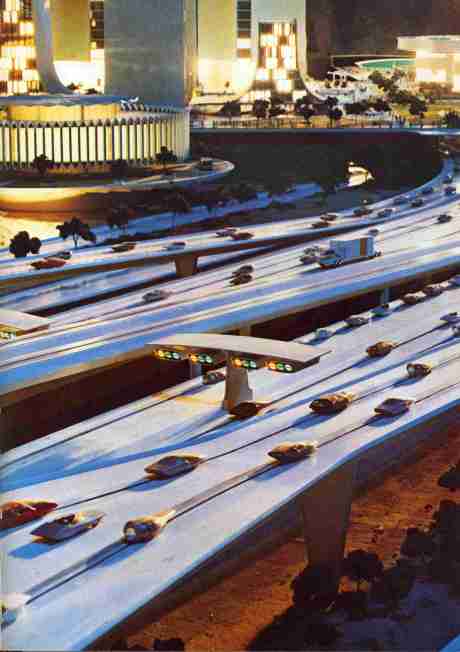

The most remarkable aspect of it was that in addition to the usual illustrations it was interspersed with photographs of a remarkable installation at the 1964/65 New York World’s Fair entitled – Futurama II. This installation was a model constructed by General Motors of their predictions for the future. Spectators would be brought through it on a ride train. As it happens, and the numerals area clue, there was a Futurama I which was shown at the 1939-40 Worlds Fair. But I knew nothing of the history of this until much much later.

As Wired Magazine commented in an article on the Futurama…

Futurama II looked even further into the future, presenting predictions of a time that most fair visitors won’t live to see. In this world, mankind had dominion over the entire universe. Six-wheeled moon buggies moved easily over the lunar surface, ritzy hotels had been built deep beneath the ocean, tree-devouring machinery carved highways through jungles. The point of view wasn’t quite as distanced as the original Futurama. The far-fetched vehicles were much larger, and they were piloted by tiny human puppets.

Either way I spent hours poring over the photographs of the Futurama. The rest of the book was good, I remember particularly vivid photographs of amoeba, an artificial heart valve, illustrations of interstellar colonists in suspended animation pods in a vast chamber inside a spaceship, full wall screens that would replace television in a truly immersive environment. And these memories were forensic. But the photographs were the gleaming heart of the book.

They depicted lunar bases, undersea colonies and most interestingly – for me at least – the City of the Future. Capital C, Capital F. This gleaming construct looked, well – it looked real. It was clear that the vehicles, gleaming darts, moved along the roadways. There was a weight to the buildings. The parks. The walkways. The windows. This might only be a model, but it was a model of a realisable future. Now I can’t quite be sure the idea that comes to mind looking at the buildings that sliding down the side of some of the more curvilinear ones would be fun is my seven year old self reaching out across the decades or just retrospective nonsense on my part now.

And I’ll bet that one Gerry Anderson paid close attention. There’s a certain something about the shape of the machines set in jungle (no worries about deforestation here) building roads that is undeniably reminiscent of the plethora of vehicles he had designed for UFO. Wired notes that:

The overall look was strikingly similar to the campy TV show Thunderbirds, which premiered as the 1964-1965 World’s Fair was closing.

You bet. Moreover I’d be almost certain that a very few years later when Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke were collaborating on 2001: A Space Odyssey they took visual cues from the designs of this exhibit. It’s not quite as antiseptic in tone, there is earth and sand and dirt, but the city doesn’t have any sense of the grime of reality.

Heady stuff, you might guess for someone in the Library of a school in a northside housing estate, and you’d be right. But then Scoil Lorcáin itself was fairly new and the Community School across the road was in its own way modernist, all exposed vents, electrical trunking and piping, like a Pompidou Centre writ small. Very very small indeed. And what of the flats across the train line? They too were examples of modernity as was the churned earth and mud of the field that I’d cross on my way home pretending I was a lunar rover (I was an oddish kid on occasion, that I’ll admit). That field later became a shopping centre. Because in its odd low level way urban Ireland in the early 1970s had a brief flash of expansion, all too rapidly stifled by the Oil Crisis, and the future was what was happening, right there and then. And although economic contraction, and slightly later adolescent cynicism, saw it become decrepit and dull within a short few years (and not just cynicism, the flats eventually saw more than their fair share of heroin users and were eventually demolished some while back) that environment remained a fading testament to a future that had at least some visionary aspects, stranded in a present of dwindling budgets, unemployment and hyper-taxation.

And I’m not unaware of the probability that it was the model aspect of these which gave them a powerful attractiveness – as well as my age. The Wired article references this:

“Detailed miniatures are always compelling,” says Dan Howland, editor of the Journal of Ride Theory. “It doesn’t matter whether they are doll houses or model trains or it’s Legoland, something about them just sucks you in.

Still, I don’t think that’s the whole story. There were other attempts to show the future. Brian Stableford and David Langford wrote The Third Millennium: A History of the World AD 2000-3000 in the early 1980s. It was interesting, but not quite as convincing (although that’s worth a post of its own). The images seemed to be that which they were, small scale models of spacecraft or machines set in diorama’s of varying degrees of credibility. These were the children of 2001, attempting to appropriate some of its often glum yet pristine magic but not quite succeeding. They didn’t have the feel, that sense of a coherent world worked out in detail and precision.

I’m fairly certain no-one would portray the future in such a way any more. Future cities are now restricted to the identikit imagery of science fiction dust-jacket illustration. I still love that. Chris Moore, Chris Foss and others provide a backdrop to my thoughts on occasion, but it’s a different sort of love from that I have for the World of Tomorrow. The vast world cities sit on the spectrum of the fantastical, Trantor or – if you prefer your pleasures on the cheap – Coruscant.

They may well be built, or may well exist elsewhere, but I’ll never know them. They’re not my future. Or yours. The World of Tomorrow, though, was. It was perhaps 2050, an unimaginable date when sitting cross-legged on the tiled floor of the Library in 1973, but one that, if I did the math, was just about feasible as a time that I’d live to see. I didn’t have any conception of what being 85 might be like, anymore than I knew what 12 would be. But that didn’t matter. It was possible. That’s all I needed to know. And, being 8 I guess I thought that the world changed more quickly than it really did. Who could blame me or legions like me, who had actual memories of seeing a man, no – two men, land at Tranquility Base? I read Speed & Power and Look and Learn. I saw the Hardy illustrations of a future that was – so it seemed – just seconds away.

Lest it seem like a vision of the future with no flaws – and in fairness it did deal with pollution and energy conservation – let me quote you the following from a description of home life:

There are smaller screens in the other rooms of the house but this is the one Mother usually uses.

When she wants to shop, she dials the store or market, and as soon as her call is answered, the store or market appears on the wall screen. She can talk to the assitants, who will show her a range of goods from clothing to the fruit bought in that day from the greenhouses in the Antarctic.

…

To pay the bills, Mother again uses the telephone which identifies the family’s account. All the money Father earns is automatically credited to his account. he never sees it, but only uses it. Mother signals the bank computer to check the amount in the accounte, just to make sure there is enough money in hand to pay the bills.

…

The newspapers we mentioned are not the kind you know. they come in over the new facsimile communications channel. Printed electrostatically on paper, they roll out of the machine, giving you an almost instant newspaper day or night. You can dial for a regular daily paper if you wish. But Mother may dial for only the women’s page features of a dozen newspapers, while Father may be more interested in the science, cultural and political news.

Of course.

Even to me, with a “Mother” who worked, and a Gran living at home who had done likewise in her time this seemed a bit odd, even old-fashioned, and even the futurist gloss of ‘Father being a spaceship designer’ toiling away in his ‘workroom’ while Mother prepared lunch appeared in its own way as fantastical – but not in a good way – as some of the other aspects of the book.

And as to why no-one would present us with such predictions any more, well I’m not entirely certain. Perhaps there has been a collective and global loss of faith in the idea that the tomorrow can, or even should, be better than today. In a world where the very shape of the continents will be changed by global warming who would casually predict what the future will hold? That’s understandable, yet I think that if true something has been lost for there was an instructive quality to that future vision.

Did the sense of wonder (natch) that came from viewing this transfer in some way from a belief that the future would be better to a belief that the future could be better? In other words did this become in some respect an element of a broader political belief system that I would then develop? The contrast between “The World of Tomorrow” and Kilbarrack, or Dublin in the 1970s was huge, yet all three were expressions of modernity, and re-reading the book (after finding it on Amazon – tellingly it seemed a lot smaller than I remembered it) the thought struck me that maybe the distinctions between the two ultimately pushed me towards some sort of political engagement, something that literally expressed progress, albeit in a somewhat different way.

It’s a bit self-serving, a bit too neat, isn’t it? Yet I’d still like to think it was so.